Yiguandao

Yiguandao's Philosophy of Universal Religious Unity

一貫道普世宗教統一哲學

Part I: Theological & Philosophical Foundations

第一部分:神學與哲學基礎

The syncretic doctrine of Yiguandao (一貫道), known as the "Unity of the Five Religions" (Wujiao Heyi, 五教合一), represents a complex and ambitious theological project that emerged from the fertile religious landscape of early 20th-century China. To comprehend this philosophy, one must first examine its foundational architecture, which rests upon the twin pillars of a supreme, maternal deity and a distinct, tripartite eschatological timeline. This framework does not merely accommodate other religions but actively reinterprets and subordinates them within a unique soteriological narrative. The core assertion is that all great religious teachings emanate from a single, primordial source, but their efficacy is historically limited. Yiguandao presents itself as the final and complete revelation of this universal truth, uniquely suited for the salvation of humanity in the current, final age. This section will deconstruct this theological foundation, exploring the central deity, the historical evolution of the unity doctrine, and the eschatological cosmology that provides both its urgency and its claim to exclusivity.

一貫道的融合教義,即「五教合一」(Wujiao Heyi),代表了一項複雜而宏大的神學工程,它誕生於二十世紀初中國豐富的宗教土壤。要理解這一哲學,必須首先審視其基礎架構,此架構立於兩大支柱之上:一位至高無上的母親神,以及一個獨特的三期末世時間論。此框架不僅僅是包容其他宗教,而是在一個獨特的救贖敘事中,主動地對它們進行重新詮釋並將其置於次要地位。其核心主張是,所有偉大的宗教教義均源自同一本源,但其效力在歷史上是有限的。一貫道將自身呈現為此普世真理的最終且完整的啟示,是特別為拯救現今末世的人類而設。本節將解構此神學基礎,探討其核心神祇、統一教義的歷史演變,以及賦予其緊迫性和排他性主張的末世宇宙觀。

1.1 The Primordial Source: The Eternal Venerable Mother and the Universal Dao

1.1 本源:無生老母與宇宙之道

At the apex of Yiguandao's cosmology and theology is a single, ultimate reality personified as the Eternal Venerable Mother, or Wusheng Laomu (無生老母), literally the "Unborn Ancient Mother". This deity, also referred to by the more formal title Míngmíng Shàngdì (明明上帝), the "Splendid Highest Deity," is conceived as the primordial source of all existence. She is a transcendent, genderless force, though the maternal title is used to emphasize her creative and merciful nature. In Yiguandao doctrine, the Mother is the universe's animating principle, the primordial energy often symbolized by fire, and is explicitly identified with the Tao in its ultimate, unlimited state of wuji (無極). A central flame, the "lantern of the Mother" (mǔdēng), is the focus of worship in all Yiguandao shrines, symbolizing her omnipresent reality.

在一貫道的宇宙觀和神學頂端,是一位單一、終極的實體,被擬人化為「無生老母」(Wusheng Laomu),字面意思是「無生之古母」。這位神祇也被更正式地稱為「明明上帝」(Míngmíng Shàngdì),即「光輝的至高神」,被認為是萬物存在的本源。她是一種超然、無性別的力量,但使用母性稱號是為了強調其創造性和慈悲的本質。在一貫道教義中,老母是宇宙的賦活原則,是常以火焰象徵的原始能量,並被明確地等同於其終極、無限狀態下的「無極」(wuji)之道。一盞中央的火焰,即「母燈」(mǔdēng),是一貫道所有佛堂的敬拜焦點,象徵著她無所不在的實體。

The movement's core mythology provides the narrative basis for its soteriological mission. According to this narrative, the Wusheng Laomu gave birth to all sentient beings, her 9.6 billion "children," from the union of yin and yang. These children, originally divine, were sent into the earthly world, where they became lost, forgot their celestial origin, and became ensnared in the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (samsara). This myth of primordial unity followed by separation and loss establishes the fundamental religious problem that Yiguandao aims to solve. The Mother, depicted as infinitely merciful, is deeply worried by the plight of her lost children and continuously seeks to guide them back to their original home, the timeless heaven known as lǐtiān (理天).

該道場的核心神話為其救贖使命提供了敘事基礎。根據此敘事,無生老母通過陰陽結合,生下了所有有情眾生,即她的九十六億「兒女」。這些原本具有神性的兒女被送到凡間,他們在此迷失,忘記了他們的天界起源,並陷入了生死輪迴(samsara)的循環中。這個關於原始統一、繼而分離與失落的神話,確立了一貫道旨在解決的根本宗教問題。被描繪為無限慈悲的老母,對她迷失兒女的困境深感憂慮,並不斷尋求引導他們回到最初的家園,即被稱為「理天」(lǐtiān)的永恆天界。

The very concept of the Wusheng Laomu is itself a product of Chinese religious syncretism, demonstrating that this method is not merely an external strategy but is embedded in the movement's most fundamental conception of divinity. The figure of the Eternal Mother evolved within Chinese folk religious traditions, particularly the "White Lotus" sectarian milieu, beginning in the 16th century when she began to supplant the older figure of the Holy Patriarch. She derives from and incorporates attributes of several key female deities in the Chinese pantheon. Her role as a primordial mother goddess connects her to Xiwangmu (西王母), the ancient Queen Mother of the West, who is associated with the mythical Mount Kunlun, the axis mundi of the world.1 Her creative aspect echoes Nüwa (女媧), the creator goddess who, in some myths, fashioned humanity. Her boundless compassion and role as a savior figure align her with the beloved bodhisattva Guanyin (觀音). This composite nature allows the Laomu to function as an all-encompassing divine figure, integrating creation, cosmic order, and compassionate salvation.

無生老母這一概念本身就是中國宗教融合主義的產物,這表明此方法不僅是一種外部策略,而是深植於該道場對神性最根本的觀念之中。無生老母的形象在中國民間宗教傳統中演變而來,特別是「白蓮教」的教派背景,始於16世紀,當時她開始取代更早的聖祖形象。她作為原始母神的角色將她與古老的西王母(Xiwangmu)聯繫起來,西王母與神話中的世界軸心崑崙山有關。她的創造者面向呼應了女媧(Nüwa),這位在某些神話中創造了人類的創世女神。她無邊的慈悲和救世主的角色,使她與備受愛戴的觀音(Guanyin)菩薩相一致。這種複合的性質使老母能夠成為一個包羅萬象的神祇形象,整合了創造、宇宙秩序和慈悲救贖。

The explicit equation of the Wusheng Laomu with the Tao is the lynchpin of Yiguandao's universalist claim. By identifying the supreme deity with the ultimate principle of the cosmos, the movement can assert that all other conceptions of ultimate reality are simply different names for this one source. Thus, the "Heaven" (Tian) revered by Confucius, the "Tao" described by Laozi, the "Buddha-nature" sought by Buddhists, the "God" worshipped by Christians, and the "Allah" of Islam are not distinct entities but culturally specific aspects or appellations of the one Laomu. This theological maneuver is the essential precondition for the entire philosophy of the "Unity of the Five Religions." It establishes a monotheistic-style foundation from which a universal religious history can be constructed. If a single, merciful deity is the source of all truth and desires the salvation of all humanity, it logically follows that she would dispatch various messengers and reveal partial truths to different peoples across history. This reframes the world's religions not as competing or contradictory systems, but as a divinely ordained series of dispensations from a common source. The founders of these religions are therefore not originators of unique truths, but transmitters of the one universal Dao, making their ultimate unity a theological necessity within the Yiguandao framework.

將無生老母與「道」明確等同,是一貫道普世主義主張的關鍵。通過將至高神與宇宙的終極原則等同起來,該道場可以宣稱所有其他關於終極實相的概念都只是這同一源頭的不同名稱。因此,孔子所尊崇的「天」、老子所描述的「道」、佛教徒所追尋的「佛性」、基督徒所敬拜的「上帝」以及伊斯蘭教的「阿拉」,都不是各自獨立的實體,而是那位獨一老母在特定文化中的面向或稱謂。這一神學操作是整個「五教合一」哲學的必要前提。它建立了一個類似一神教的基礎,並由此可以構建一部普世的宗教歷史。如果一位單一、慈悲的神是所有真理的源頭,並渴望全人類的救贖,那麼合乎邏輯的推論是,她會在歷史長河中派遣各種信使,向不同民族揭示部分的真理。這將世界各大宗教重新定義為並非相互競爭或矛盾的體系,而是一系列由共同源頭神聖命定的天命傳承。因此,這些宗教的創始人並非獨特真理的開創者,而是那唯一的普世之道的傳遞者,這使得他們的最終統一在一貫道的框架內成為一種神學上的必然。

1.2 From Three to Five: The Evolution of Wujiao Heyi

1.2 從三教到五教:五教合一的演變

The doctrine of the "Unity of the Five Religions" (wujiao heyi) is a distinctly modern innovation, representing an early 20th-century expansion of a much older Chinese syncretic tradition: the "Unity of the Three Teachings" (sanjiao heyi, 三教合一). For centuries, Chinese intellectual and popular religious thought had sought to harmonize the teachings of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, viewing them as complementary expressions of a single, underlying truth or Way. In the turbulent final years of the Qing dynasty and the early Republican period (early 20th century), this framework was expanded by a number of new religious movements, often termed "redemptive societies" by scholars, to include Christianity and Islam. This expansion was a direct response to the dramatically increased presence of these global religions in China, driven by Western missionary activity and a growing consciousness of China's place in a world of diverse nations and faiths. For any movement aspiring to a universal message, it became theologically and strategically necessary to account for these prominent world faiths. The wujiao heyi formula provided a means to do so, domesticating these "foreign" traditions by incorporating them into a familiar syncretic structure that ultimately affirmed the primacy of the Chinese-derived Dao as their common source.

「五教合一」(wujiao heyi)的教義是一項獨特的現代創新,是二十世紀初對一個更古老的中國融合傳統——「三教合一」(sanjiao heyi)的擴展。數百年來,中國的知識界和民間宗教思想一直試圖調和儒、道、釋三教的教義,視其為同一根本真理或「道」的互補表達。在清朝末年和民國初期(二十世紀初)的動盪歲月中,一些新興宗教運動(常被學者稱為「救世團體」)擴展了此框架,將基督教和伊斯蘭教也納入其中。這一擴展是對這些全球性宗教在中國顯著增長的直接回應,其背後驅動力是西方的傳教活動以及中國對自身在一個多元國家與信仰世界中地位的日益覺醒。對於任何渴望傳遞普世信息的運動而言,將這些顯著的世界信仰納入考量在神學和策略上都變得至關重要。「五教合一」的模式提供了一種方法,通過將這些「外來」傳統納入一個熟悉的融合結構中,從而將其本土化,並最終肯定了源於中國的「道」作為它們共同來源的首要地位。

Yiguandao was one of the foremost proponents of this new five-fold unity. The movement traces its lineage back to the Xiantiandao (先天道), or "Way of Former Heaven," a network of popular salvationist sects that emerged in the 17th and 18th centuries and also taught a syncretic doctrine centered on the Wusheng Laomu and a three-stage eschatology. The formal establishment of Yiguandao in its modern form is attributed to its fifteenth patriarch, Wang Jueyi (王覺一, 1821-1886), who in the late 19th century extensively reformed the sect's teachings and rituals, infusing them with a strong Neo-Confucian orientation. This "Confucianization" laid a critical foundation for the movement's later development and its strategies for gaining social legitimacy. The name Yiguandao (一貫道) was officially adopted in 1905 by the sixteenth patriarch, Liu Qingxu (劉清虛).

一貫道是這一新五教合一理念最重要的倡導者之一。該道場的道統可追溯至「先天道」(Xiantiandao),即「昔日之天道」,這是一個在17和18世紀興起的民間救贖教派網絡,同樣教導以無生老母和三期末劫論為中心的融合教義。一貫道現代形式的正式確立歸功於其第十五代祖師王覺一(1821-1886),他在19世紀末對教派的教義和儀式進行了廣泛改革,並為其注入了強烈的新儒家導向。這種「儒家化」為該道場後來的發展及其爭取社會合法性的策略奠定了關鍵基礎。「一貫道」(Yiguandao)這個名稱於1905年由第十六代祖師劉清虛正式採用。

The name itself is a declaration of the movement's philosophical mission. Yiguandao, meaning the "Consistent Way" or "Way of Pervading Unity," is a direct quotation from the Confucian Analects (Book 4, Chapter 15), where Confucius tells his disciple, "My way has a single thread that runs through it" (吾道一以貫之, wú dào yī yǐ guàn zhī). By adopting this name, the movement positions itself as the ultimate inheritor and synthesizer of this universal, unifying principle that Confucius spoke of. It claims not just to be a way, but the way that reveals the single truth underpinning all other teachings.

這個名字本身就是對該道場哲學使命的宣言。一貫道,意為「一貫之道」或「貫通統一之道」,直接引自《論語·里仁篇》,其中孔子對其弟子說:「吾道一以貫之」。通過採用此名,該道場將自己定位為孔子所言之普世統一原則的最終繼承者和集大成者。它不僅聲稱是一條道路,更是那揭示所有其他教義背後單一真理的唯一道路。

This claim, however, is not one of equal partnership but of supersession. Yiguandao's philosophy holds that while the five great religions are authentic, partial expressions of the Dao, their followers have, over the centuries, lost their way, forgotten the fundamental unity of their founders' messages, and become mired in narrow-minded dogma and moral decay. Yiguandao therefore presents itself as a new dispensation, a final and complete revelation of the universal truth made necessary by the world's degenerate state. It is the ultimate fulfillment of the partial truths taught by the other religions, offering the only true path to salvation in the current age. This dual posture of honoring the five religions while simultaneously claiming to supersede them is a central and defining characteristic of Yiguandao's syncretic philosophy.

然而,此主張並非平等合作,而是取而代之。一貫道的哲學認為,雖然五大宗教是「道」的真實但片面的表達,但其信徒在數個世紀中已迷失方向,忘記了其創始人信息的根本統一性,並陷入了狹隘的教條和道德敗壞之中。因此,一貫道將自己呈現為一個新的天命,一個因世界墮落狀態而變得必要的、對普世真理的最終且完整的啟示。 它是對其他宗教所教導的部分真理的終極實現,提供了現今時代唯一的真正救贖之道。這種既尊重五教又同時聲稱取而代之的雙重姿態,是一貫道融合哲學的核心及決定性特徵。

1.3 The Final Dispensation: Eschatology of the Three Eras

1.3 最終的普渡:三期末劫論

The mechanism that transforms Yiguandao's syncretic philosophy into an exclusivist program of salvation is its distinct eschatological cosmology. Inherited and adapted from its Xiantiandao precursors, this doctrine divides all of human history into a cycle of three cosmic periods, or "Yang Eras" (qi, 氣), each with its own presiding deity and method of salvation. This temporal, hierarchical framework is the engine that drives Yiguandao's soteriological urgency and its claim to be the sole ark of salvation in the modern world.

將一貫道的融合哲學轉變為排他性救贖方案的機制,是其獨特的末世宇宙觀。此教義繼承並改編自其先天道的前身,將整個人類歷史劃分為三個宇宙時期的循環,即「陽期」(qi,氣),每個時期都有其掌管的神祇和救贖方法。

這個時間性的、等級化的框架,是驅動一貫道救贖緊迫感及其聲稱是現代世界唯一救贖方舟的引擎。

The three eras are as follows:

三期如下:

- The Green Yang Era (Qingyang Qi, 青陽期): This was the first historical epoch, presided over by the Dīpankara Buddha (燃燈佛, Rándēng Fó). During this ancient period, the Dao was transmitted secretly, and salvation was accessible only to a very select few, such as rulers and high officials.

- 青陽期(Qingyang Qi):這是第一個歷史時代,由燃燈佛(Rándēng Fó)掌管。在這個遠古時期,道是秘密傳授的,只有極少數人,如統治者和高級官員,才能獲得救贖。

- The Red Yang Era (Hongyang Qi, 紅陽期): This second epoch was presided over by the historical Gautama Buddha (釋迦牟尼佛, Shìjiāmóuní Fó). In this era, the Dao was more widely disseminated, but salvation was still primarily available to dedicated religious practitioners and cultivators. Within this framework, Yiguandao places the missions of Jesus Christ and the Prophet Muhammad, viewing their teachings as part of the Red Yang dispensation.

- 紅陽期(Hongyang Qi):第二個時代由歷史上的釋迦牟尼佛(Shìjiāmóuní Fó)掌管。在這個時代,道被更廣泛地傳播,但救贖仍然主要提供給虔誠的宗教修行者。在此框架內,一貫道將耶穌基督和先知穆罕默德的使命置於其中,視他們的教義為紅陽期普渡的一部分。

- The White Yang Era (Baiyang Qi, 白陽期): This is the current and final era of history, which Yiguandao dates as having begun around 1912. This period is described as the time of the final cataclysm or apocalypse (

mojie, 末劫), an age of unprecedented moral decay, social chaos, and natural disasters. However, it is also the time of the third and final universal salvation, when the true Dao is made available to all of humanity for the last time. This ultimate dispensation is presided over by the Maitreya Buddha (彌勒佛, Mílè Fó), the messianic "future Buddha" of Buddhist tradition, whom Yiguandao teaches has already descended to inaugurate this final chance for redemption.

- 白陽期(Baiyang Qi):這是當前且最後的歷史時代,一貫道將其開端定於1912年左右。此時期被描述為末劫(mojie)時期,一個道德空前敗壞、社會混亂和天災人禍的時代。然而,這也是第三次也是最後一次普渡救贖的時期,屆時真道將最後一次向全人類開放。這次最終的普渡由彌勒佛(Mílè Fó)掌管,他是佛教傳統中的彌賽亞式「未來佛」,一貫道教導他已降世,開啟這最後的救贖機會。

This eschatological narrative is crucial because it provides a powerful justification for Yiguandao's existence and its missionary zeal. The belief that the world is in its final, decadent phase imbues the movement with a profound sense of urgency. Adherents see the calamities of the modern world as signs of the mojie and believe it is their imperative duty to rescue people from suffering by transmitting the Dao (chuandao, 傳道). This mission, called pǔdù sān cáo (普渡三曹), aims for the universal salvation of all beings—those in heaven, the spirits of the dead in the underworld, and living humanity on Earth.

這個末世論敘事至關重要,因為它為一貫道道的存在及其傳教熱情提供了有力的理據。相信世界正處於其最後的頹敗階段,為該道場注入了一種深刻的緊迫感。信徒將現代世界的災難視為末劫的徵兆,並相信通過傳道(chuandao)來拯救人們脫離苦難是他們義不容辭的責任。此使命被稱為「普渡三曹」(pǔdù sān cáo),旨在普救所有眾生——天上的氣天神、地府的亡靈以及人間的芸芸眾生。

The doctrine of the Three Eras effectively resolves the potential contradiction between honoring other religions and claiming exclusive access to salvation. While the philosophy of Wujiao Heyi establishes that all religions share a common source in the Eternal Mother, the eschatological framework organizes them into a historical hierarchy. The teachings of the Green and Red Yang Eras—including orthodox Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam—are respected as valid parts of the Mother's divine plan for those past ages. However, they are now framed as historically contingent, incomplete, and, most importantly, soteriologically obsolete. With the dawn of the White Yang Era, a new presiding Buddha (Maitreya) has taken charge, and a new, complete method of salvation—the transmission of the Dao through Yiguandao's initiation—has been revealed. Therefore, while followers of other faiths may be living moral lives, their paths are no longer considered effective for escaping the final calamity and returning to the Mother. This logic positions Yiguandao not as one valid path among many, but as the only valid path for the current age, transforming a philosophy of syncretic unity into a practice of soteriological exclusivity.

三期論的教義有效地解決了尊重其他宗教與主張獨家救贖權之間的潛在矛盾。儘管五教合一的哲學確立了所有宗教都源於無生老母這一共同源頭,但末世論框架將它們組織成一個歷史性的等級體系。青陽期和紅陽期的教義——包括正統的佛教、基督教和伊斯蘭教——被尊重為老母對過去時代神聖計劃的有效部分。然而,現在它們被定義為具有歷史偶然性、不完整,且最重要的是,在救贖論上已經過時。隨著白陽期的來臨,一位新的掌盤佛(彌勒佛)已接管,一種新的、完整的救贖方法——通過一貫道的求道儀式傳承大道——已經被揭示。因此,儘管其他信仰的追隨者可能過著道德的生活,但他們的道路已不再被認為是逃離末劫、回歸老母身邊的有效途徑。這種邏輯將一貫道定位為不是眾多有效道路中的一條,而是當前時代唯一有效的道路,從而將一種融合統一的哲學轉變為一種救贖排他性的實踐。

Part II: The Syncretic Method In Practice

第二部分:融合方法的實踐

The philosophical and theological architecture of Yiguandao finds its practical expression in a sophisticated and systematic method of syncretism. This method is not a simple amalgamation of disparate beliefs but a coherent process of appropriation, reinterpretation, and ritualization. It operates by identifying the founders of the five great religions as subordinate messengers of a higher power, subjecting their scriptures to an esoteric exegesis that reveals a hidden Yiguandao truth, and embodying this synthesized understanding in a unique set of rituals and ethical precepts. This section will analyze these practical dimensions, examining how Yiguandao absorbs the authority of other traditions to legitimize its own, and how it translates its abstract philosophy of unity into the lived experience of its followers through a distinct path of cultivation and salvation.

一貫道的哲學和神學架構,通過一種複雜而系統的融合方法找到了其實踐表達。此方法並非對不同信仰的簡單混合,而是一個連貫的挪用、重新詮釋和儀式化過程。其運作方式是將五大宗教的創始人視為更高力量的次級信使,對其經文進行秘傳式的解經,以揭示隱藏的一貫道真理,並將這種綜合的理解體現在一套獨特的儀式和倫理戒律中。本節將分析這些實踐層面,檢視一貫道如何吸收其他傳統的權威以使自身合法化,以及它如何通過一條獨特的修行和救贖之路,將其抽象的統一哲學轉化為其信徒的生活體驗。

2.1 A Pantheon of Sages: The Re-Positioning of Religious Founders

2.1 聖哲的殿堂:宗教創始人的重新定位

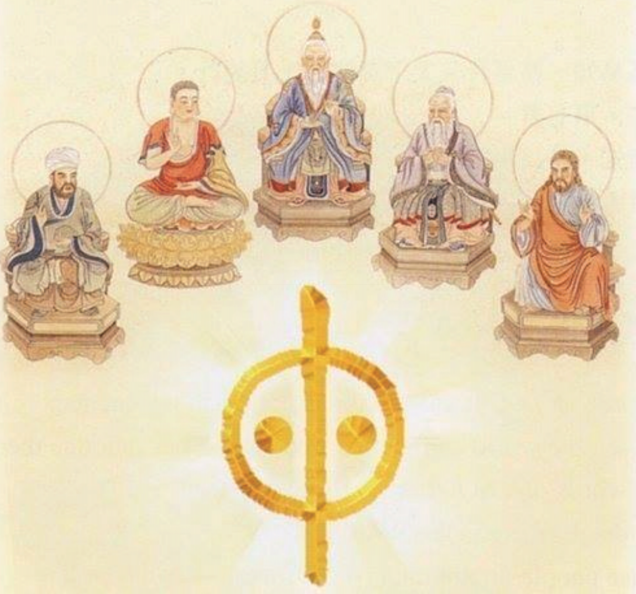

Central to Yiguandao's syncretic method is its re-positioning of the world's major religious founders. Figures such as Confucius, Laozi, Gautama Buddha, Jesus Christ, and the Prophet Muhammad are not dismissed but are honored and integrated into the Yiguandao worldview. However, they are stripped of their ultimate authority and reframed as a cohort of "Sages" or prophets, each sent by the one Eternal Mother to establish teachings suitable for a specific culture, time, and place. In this schema, they are essentially peers, all standing below the supreme authority of the Wusheng Laomu. This approach allows Yiguandao to acknowledge their historical importance while simultaneously subordinating their missions to its own grander, final narrative.

一貫道融合方法的核心在於其對世界主要宗教創始人的重新定位。孔子、老子、釋迦牟尼佛、耶穌基督和先知穆罕默德等人物並未被摒棄,而是受到尊崇並被整合到一貫道的世界觀中。然而,他們被剝奪了終極權威,而被重新定義為一群「聖人」或先知,每一位都是由獨一的無生老母派遣,為特定的文化、時間和地點建立合適的教義。在這個體系中,他們基本上是同儕,都位列於無生老母的至高權威之下。這種方法使一貫道既能承認他們的歷史重要性,又能同時將他們的使命置於自己更宏大、更終極的敘事之下。

The most detailed example of this process within the available material is the integration of Jesus Christ. Yiguandao teachings, particularly those received through spirit-writing, present Jesus as a sage who received a heavenly command to be born in the West and establish Christianity. His core teaching is summarized as "cleansing the mind and shifting one’s nature, praying quietly and being close to the One" and transforming humanity through "love without distinction". However, his mission is explicitly defined as partial and preparatory. According to Yiguandao doctrine, the time was not yet "ripe" during his life for the full and true "mind dharma" (xīnfǎ, 心法)—the direct, esoteric transmission of the Dao—to be revealed. Consequently, his crucifixion is radically reinterpreted. It is not seen as the ultimate act of atonement for sin, as in Christian theology, but as a divinely ordained measure to prevent the premature divulging of heavenly secrets before the appointed time. In this view, Jesus was recalled to Heaven to safeguard the final truth for a later age. Furthermore, in Yiguandao spirit-writing séances—a key source of doctrinal authority—figures claiming to be Jesus appear and criticize the "narrow-mindedness" of his followers, urging them to abandon the limitations of institutional Christianity and embrace the complete and final truth of the Great Dao, which is now being made available exclusively through Yiguandao. This is a powerful legitimizing strategy, as it co-opts the authority of the founder of Christianity to validate his own supersession.

在現有資料中,關於此過程最詳細的例子是對耶穌基督的整合。一貫道的教義,特別是通過扶乩接收的教義,將耶穌呈現為一位領受天命降生於西方並創立基督教的聖人。他的核心教導被總結為「洗心移性、默禱親一」以及通過「愛無差等」來轉化人性。然而,他的使命被明確定義為是片面的和預備性的。根據一貫道的教義,在他生前時機尚未「成熟」,無法揭示完整且真實的「心法」(xīnfǎ)——即道的直接、秘傳的傳承。因此,他的受難被徹底地重新詮釋。它不被視為像基督教神學那樣為罪作出的終極贖罪行為,而是被看作是神聖命定的措施,以防止在指定時間之前過早洩露天機。在此觀點中,耶穌被召回天堂,是為了為後世保護最終的真理。此外,在一貫道作為教義權威關鍵來源的扶乩儀式中,自稱耶穌的靈體會顯現,並批評其追隨者的「狹隘」,敦促他們放棄制度化基督教的局限,擁抱大道的完整與最終真理,而此真理現正由一貫道獨家提供。這是一種強而有力的合法化策略,因為它借用了基督教創始人的權威來驗證其自身的被取代性。

In stark contrast, the integration of the Prophet Muhammad and Islam is far less theologically developed. While Muhammad is consistently named as one of the five founding sages and Islam is included in the wujiao heyi formula, the available research provides no specific reinterpretations of his life, the Quran, or Islamic theology comparable to the detailed exegesis applied to Christianity. In related "unity sects" like the Daoyuan, an altar might feature a tablet with Muhammad's name alongside the other four founders, all under the principal deity. This inclusion appears to be more declarative and structural than deeply integrated. This "Islamic gap" is itself a significant data point. It suggests that Yiguandao's syncretism is not a uniform academic exercise but a pragmatic and historically contingent process. The movement's formative years in Republican China were marked by intense engagement and competition with Christian missionaries, which provided both the impetus and the textual material for a detailed theological response. Islam, while long-present in China through communities like the Hui people, was not the primary religious interlocutor or rival for the salvationist sects of Shandong and North China where Yiguandao grew. Therefore, Islam was likely incorporated into the "five religions" framework primarily for the sake of ideological completeness, to bolster the claim of universality, without the same perceived need for deep theological engagement and appropriation that was directed at Christianity.

與此形成鮮明對比的是,對先知穆罕默德和伊斯蘭教的整合在神學上遠不夠發達。儘管穆罕默德一直被列為五位創教聖人之一,伊斯蘭教也被納入「五教合一」的公式中,但現有研究並未提供任何關於其生平、《古蘭經》或伊斯蘭神學的具體重新詮釋,無法與應用於基督教的詳細解經相提並論。在相關的「合一教派」如道院中,祭壇上可能會擺放一個刻有穆罕默德名字的牌位,與其他四位創教聖人並列,皆置於主神之下。這種包含似乎更多是宣告性和結構性的,而非深度整合的。這個「伊斯蘭教的空白」本身就是一個重要的數據點。這表明一貫道的融合主義並非一項統一的學術實踐,而是一個務實且受歷史制約的過程。該道場在民國時期的形成歲月,以與基督教傳教士的激烈互動和競爭為標誌,這為其詳細的神學回應提供了動力和文本材料。而伊斯蘭教,雖然通過回族等社群在中國長期存在,但對於一貫道成長的山東和華北地區的救贖教派而言,並非主要的宗教對話者或競爭對手。因此,伊斯蘭教被納入「五教」框架,很可能主要是為了意識形態上的完整性,以支持其普世性的主張,而沒有像針對基督教那樣,感到有進行深度神學互動和挪用的同樣需求。

Despite the rhetoric of five-fold unity, the Yiguandao pantheon and leadership structure remain firmly rooted in the Chinese religious context. The movement's modern patriarchs, Zhang Tianran (張天然) and Sun Suzhen (孫素貞), are venerated as divine beings themselves. Zhang is widely considered to be an incarnation of the "Living Buddha Jigong" (濟公活佛), a popular, eccentric Daoist-Buddhist deity, while Sun is seen as a reincarnation of the bodhisattva Guanyin. Ultimately, the designated savior for the current White Yang Era is Maitreya Buddha, a messianic figure of central importance in East Asian Buddhism. This hierarchical arrangement, where Chinese patriarchs and deities hold the keys to salvation for the final age, demonstrates that Yiguandao's syncretism is a process of hierarchical absorption. It honors foreign sages only to frame their work as a prelude to the final, superior truth revealed through its own Chinese-based lineage.

儘管有五教合一的說辭,一貫道的神祇體系和領導結構仍然牢固地植根於中國的宗教背景中。該道場的現代祖師張天然和孫素貞本身就被尊為神明。張天然被廣泛認為是廣受歡迎、行為古怪的道釋神祇「濟公活佛」的化身,而孫素貞則被視為觀音菩薩的轉世。最終,為當前白陽期指定的救世主是彌勒佛,這是一位在東亞佛教中具有核心重要性的彌賽亞式人物。這種等級森嚴的安排,由中國的祖師和神祇掌握著末世救贖的鑰匙,表明一貫道的融合主義是一個等級吸收的過程。它尊崇外國聖人,僅僅是為了將他們的功業界定為一個前奏,為其自身基於中國的道統所揭示的最終、更優越的真理鋪路。

2.2 Unsealing the Scriptures: Esoteric Exegesis of Global Holy Texts

2.2 解封經文:全球聖典的秘傳解經

Yiguandao's approach to the holy texts of other religions mirrors its treatment of their founders. It does not reject scriptures like the Bible or the Quran but claims to possess the key to their true, hidden meaning. This method of esoteric exegesis posits that these texts, composed in a previous era, contain veiled references and prophecies pointing toward the coming of the Dao and the mission of Yiguandao. From the perspective of outsiders and followers of the original faiths, this practice is often seen as a distortion of the sacred verses to fit a preconceived narrative.

一貫道對待其他宗教聖典的方式,反映了其對待這些宗教創始人的方式。它不排斥如《聖經》或《古蘭經》等經文,而是聲稱擁有解開其真實、隱藏意義的鑰匙。這種秘傳解經的方法假定,這些在先前時代寫成的文本,包含了指向「道」的降臨和一貫道使命的隱晦引述和預言。從局外人和原始信仰追隨者的角度來看,這種做法常被視為為了迎合一個預設的敘事而扭曲神聖經文。

The reinterpretation of the Christian Bible provides the clearest illustration of this method. Yiguandao texts perform a symbolic deconstruction of core Christian imagery. For instance, the cross is not viewed as a symbol of sacrifice and redemption but is reinterpreted as a cryptic map of the human body, with the central point of the cross hinting at the location of the xuanguan (玄關), or "mysterious pass." This xuanguan is the spiritual aperture or "heavenly portal" on the forehead that is physically pointed out by an initiator during the secret Yiguandao rite of transmission. Biblical passages are read through this lens. Jesus's teaching that "the kingdom of God is within you" Luke 17:21 is taken not as a metaphorical statement about inner spirituality but as a literal reference to this specific, internal point on the body. The two criminals crucified alongside Jesus are interpreted as representing the two eyes, further reinforcing the focus on the head as the location of this sacred gateway.

對基督教《聖經》的重新詮釋為此方法提供了最清晰的例證。一貫道的文本對核心的基督教意象進行了符號性的解構。例如,十字架不被視為犧牲和救贖的象徵,而是被重新詮釋為人體的神秘地圖,十字架的中心點暗示著「玄關」的位置。這個玄關是位於前額的靈性竅門或「天門」,在秘密的一貫道傳道儀式中由點傳師親手指點。《聖經》的段落是通過這個視角來解讀的。耶穌在《路加福音》17:21中教導的「神的國就在你們心裡」,不被視為關於內在靈性的比喻性陳述,而是被當作對身體上這個特定內在點的字面指涉。與耶穌一同被釘十字架的兩名罪犯被詮釋為代表兩隻眼睛,進一步強化了頭部作為此神聖門戶所在地的焦點。

This exegetical method is also used to subordinate Christian messianic prophecies to Yiguandao's own timeline. A prominent example is the re-reading of John the Baptist's declaration in Matthew 3:11: "he that cometh after me is mightier than I,." In Christian tradition, this clearly refers to Jesus. In Yiguandao's esoteric reading, however, it is claimed that John was not referring to Jesus, but to a figure of the next dispensation: the Living Buddha Jigong, the very deity that the eighteenth patriarch, Zhang Tianran, was believed to embody. This reinterpretation cleverly positions Jesus as an intermediate figure, a forerunner not to his own fulfillment in Christian theology, but to the true savior of the final age, who is linked directly to the leadership of Yiguandao.

這種解經方法也被用來將基督教的彌賽亞預言置於一貫道自身的時間線之下。一個顯著的例子是重讀施洗約翰在《馬太福音》3:11中的宣告:「那在我以後來的,能力比我更大。」在基督教傳統中,這顯然是指耶穌。然而,在一貫道的秘傳解讀中,聲稱約翰所指的並非耶穌,而是下一個普渡時期的代表人物:濟公活佛,也就是第十八代祖師張天然所化身的那位神祇。這種重新詮釋巧妙地將耶穌定位為一個中間人物,不是為基督教神學中自身的應驗鋪路,而是為末世的真正救世主作先鋒,而這位救世主則直接與一貫道的領導層相連。

Alongside these reinterpretations of external scriptures, Yiguandao possesses its own extensive body of sacred texts. A significant portion of this canon has been received through the practice of spirit-writing, known as fuji (扶乩) or fuluan (扶鸞), where messages from deities are transmitted through a medium and transcribed. This method, inherited from Xiantiandao and common in Chinese popular religion, provides a continuous stream of divine revelation and legitimizes the teachings and leadership of the movement. Key scriptures that form the basis of Yiguandao teaching and practice include the Maitreya Salvation Sutra (彌勒救苦真經) and the Hundred Filials Sutra (百孝經). In a move toward modernization and systematization, these and other texts have been compiled in recent years into a formal Yiguandao Canon (一貫道藏, Yīguàndào zàng), which aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic overview of the group's doctrines.

除了對外部經文的這些重新詮釋外,一貫道也擁有自己大量的神聖文本。此經藏中有相當一部分是通過扶乩或扶鸞的實踐接收的,即由神靈透過媒介傳遞訊息並被記錄下來。這種方法繼承自先天道,並在中國民間宗教中很常見,它提供了一股持續的神聖啟示流,並使該道場的教義和領導層合法化。構成一貫道教義和實踐基礎的關鍵經文包括《彌勒救苦真經》和《百孝經》。為了邁向現代化和系統化,這些以及其他文本近年來被彙編成正式的《一貫道藏》,旨在對該團體的教義提供一個全面而系統的綜覽。

2.3 The Embodied Path: Ritual, Ethics, and the Three Treasures

2.3 體現之道:儀式、倫理與三寶

The theology of Yiguandao is not merely an abstract system of belief but is actualized through a distinct path of cultivation, centered on a pivotal initiation ritual and a syncretic ethical code. The ultimate goal is to transcend the cycle of rebirth and return to the Eternal Mother, a salvation made possible only through direct transmission of the Dao.

一貫道的神學不僅僅是一個抽象的信仰體系,而是通過一條獨特的修行道路來實現的,其核心是一個關鍵的入教儀式和一套融合的倫理規範。最終目標是超越輪迴,回歸無生老母,這一救贖只有通過道的直接傳承才可能實現。

The most important and indispensable ritual in Yiguandao is the initiation ceremony, known as Qiu Dao (求道), which translates to "Seeking the Dao". This ceremony is considered the sole gateway to salvation in the current White Yang Era and is the defining moment for every member. It is an exclusive rite that articulates the boundary between the saved (initiates) and the unsaved. During the Qiu Dao ceremony, the new member is granted the "Three Treasures" (Sanbao, 三寶), which are described as the saving grace offered directly by the Wusheng Laomu. The precise meaning and application of the Three Treasures are held as a strict secret, prohibited from being shared with non-initiates, and are used by members in daily life as a form of meditation and a means of spiritual protection.

此儀式被視為當前白陽期唯一的救贖門戶,是每位成員的決定性時刻。這是一個排他性的儀式,劃分了得救者(求道者)與未得救者之間的界線。在求道儀式中,新成員會被授予「三寶」(Sanbao),這被描述為無生老母直接賜予的救贖恩典。三寶的確切含義和應用被視為嚴格的秘密,禁止與未入道者分享,並由成員在日常生活中用作一種冥想形式和精神保護的手段。

The Three Treasures are:

三寶是:

- The Xuanguan (玄關): The "Mysterious Pass" or "Heavenly Portal." This involves the initiator, a "Transmitting Master" (dianchuanshi) who holds the Heavenly Decree (tianming), physically pointing to a specific spot on the initiate's forehead, believed to be the aperture through which the soul enters and leaves the body. This act is thought to open the direct path to heaven.

- 玄關:即「神秘之關」或「天門」。此儀式涉及一位持有天命的「點傳師」(dianchuanshi),他會親手指點求道者前額上的一個特定點,該點被認為是靈魂進出肉體的竅門。此舉被認為能打開直達天堂的道路。

- The Koujue (口訣): The "Verbal Formula" or mantra. This is a secret, five-character incantation that is whispered to the initiate. It is believed to be a password that allows the soul to bypass the guardians of the afterlife and enter heaven.

- 口訣:即「口頭真言」或真言。這是一段秘密的五字真言,會悄聲傳授給求道者。據信,這是一個能讓靈魂繞過地府守衛、進入天堂的密碼。

- The Hetong (合同): The "Hand Sign" or mudra. This is a specific hand gesture, resembling a child bowing, that serves as a sign of recognition in the celestial realm, identifying the soul as one of the Mother's children who has received the Dao.

- 合同:即「手印」。這是一種特定的手勢,狀似孩童作揖,作為在天界的識別標誌,表明該靈魂是已得道的老母兒女之一。

Together, these Three Treasures are believed to provide an absolute guarantee of salvation, enabling the soul of an initiate to transcend the circle of birth and death and ascend directly to lǐtiān upon death.

這三寶被認為共同提供了一種絕對的救贖保證,使求道者的靈魂在死後能夠超脫生死輪迴,直升理天(lǐtiān)。

Beyond this pivotal ritual, the daily life of a Yiguandao practitioner is guided by a syncretic ethical framework that draws its core tenets from the five religions. This moralizing doctrine emphasizes self-cultivation as an opportunity for repentance and purification in the face of the final era's calamities.

除了這個關鍵儀式之外,一貫道修行者的日常生活受到一個融合倫理框架的指導,其核心信條來自五大宗教。這種道德化的教義強調自我修養,視其為在末世災難面前懺悔和淨化的機會。

Confucianism provides the primary structure for social ethics. Adherents are expected to embody Confucian virtues, particularly the "Five Relationships" (ruler-subject, father-son, husband-wife, elder-younger brother, friend-friend) and the "Eight Virtues" (loyalty, filial piety, benevolence, love, faithfulness, justice, harmony, and peace). This strong emphasis on Confucian morality has also served as a crucial political strategy, allowing the group to present itself as a conservative force for social stability and a preserver of traditional Chinese culture, thereby defusing tensions with state authorities.

儒家思想為社會倫理提供了主要結構。信徒被期望體現儒家美德,特別是「五倫」(君臣、父子、夫婦、兄弟、朋友)和「八德」(忠、孝、仁、愛、信、義、和、平)。這種對儒家道德的強烈重視,也成為一項關鍵的政治策略,使該團體能夠將自己呈現為一個促進社會穩定的保守力量和傳統中華文化的維護者,從而化解與國家當局的緊張關係。

Buddhism contributes key elements of personal practice and cosmology. The most prominent of these is vegetarianism, which is considered a fundamental practice for purifying the body and spirit, cultivating compassion by avoiding the killing of sentient beings, and cleansing karmic debts. The overarching belief in karma and reincarnation provides the context for the urgency of salvation. The ultimate goal is often described using Buddhist terminology, such as achieving a "Pure Land in the human realm" (renjian jingtu).

佛教為個人修行和宇宙觀貢獻了關鍵元素。其中最突出的是素食主義,這被認為是淨化身心、通過避免殺害有情眾生來培養慈悲心、以及清除業債的根本修行。對業力和輪迴的普遍信仰為救贖的緊迫性提供了背景。最終目標常使用佛教術語來描述,例如實現「人間淨土」(renjian jingtu)。

Taoism informs the concepts of self-cultivation and cosmic harmony. The goal of aligning oneself with the universal Dao is a core principle, and some teachings draw on concepts from Taoist internal alchemy (neidan), which uses meditative practices to refine the body's energies and nurture a spiritual self.

道家思想為自我修養和宇宙和諧的概念提供了信息。與普世之道保持一致的目標是核心原則,一些教義借鑒了道家內丹術(neidan)的概念,即運用冥想練習來煉化身體能量,培養靈性自我。

Rituals are an integral part of this cultivation. Daily or regular practice involves prayers, chanting, and prostrations before a shrine (fotang, 佛堂), which can range from a small altar in a private home to a large public temple. The central focus of the altar is the mudeng (母燈), the lamp representing the Eternal Mother, often flanked by statues of key deities like Maitreya, Jigong, and Guanyin. These rituals are understood not as transactions to request blessings, but as practices of humility, gratitude for the grace already received, and reflection on one's moral conduct in relation to the virtues embodied by the deities.

儀式是這種修行的重要組成部分。每日或定期的修行包括在佛堂(fotang)前祈禱、誦經和叩拜,佛堂的規模可以從家中的小祭壇到大型的公共廟宇不等。祭壇的中心焦點是母燈(mudeng),即代表無生老母的燈,其兩側常擺放著彌勒、濟公和觀音等主要神祇的雕像。這些儀式不被理解為祈求福報的交易,而是被看作是謙卑、對已獲恩典的感恩,以及對照神祇所體現的美德反思自身道德行為的修行。

Part III: Comparative & Critical Perspectives

第三部分:比較與批判性視角

To fully grasp the nature of Yiguandao's philosophy of unity, it is essential to situate it within a broader context. This involves comparing its syncretic model with other, similar new religious movements (NRMs) to highlight its distinctive features. It also requires an examination of the critical responses it has elicited from established religious institutions, state authorities, and academic observers. This comparative and critical lens reveals that Yiguandao's theology is not only a system of belief but also a dynamic strategy for survival, legitimation, and expansion in a world that has often been hostile to its existence. The very syncretism that defines its identity has been both the source of its appeal and the justification for its persecution.

要完全掌握一貫道統一哲學的本質,必須將其置於更廣闊的背景中進行考察。這包括將其融合模式與其他類似的新興宗教運動(NRMs)進行比較,以突顯其獨特之處。這也需要審視它從既有宗教機構、國家當局和學術觀察者那裡引發的批判性回應。這種比較性和批判性的視角揭示,一貫道的神學不僅是一個信仰體系,也是在一個常常對其存在懷有敵意的世界中,一種求生存、合法化和擴張的動態策略。定義其身份的融合主義本身,既是其吸引力的來源,也是其遭受迫害的理由。

3.1 Parallels in Unity: Yiguandao, Caodaism, and the Baha'i Faith

3.1 統一的相似之處:一貫道、高台教與巴哈伊信仰

Yiguandao is not unique in its claim to unify the world's religions. It belongs to a class of modern NRMs, emerging in the 19th and early 20th centuries, that responded to an age of increasing globalization and inter-religious contact by proposing a universal, syncretic faith. Comparing Yiguandao with two other prominent examples—Caodaism from Vietnam and the Baha'i Faith from Persia—illuminates the specific character of its unifying philosophy. While all three share a belief in a single God, a history of progressive revelation, and a mission to unite humanity, they differ significantly in their theological logic, soteriological claims, and cultural roots.

一貫道在其統一世界宗教的主張上並非獨一無二。它屬於一類現代新興宗教運動,興起於19世紀和20世紀初,它們通過提出一種普世的、融合的信仰來回應一個全球化日益加劇和宗教間接觸增多的時代。將一貫道與另外兩個著名的例子——越南的高台教和波斯的巴哈伊信仰——進行比較,可以闡明其統一哲學的具體特徵。雖然三者都相信一位獨一的神、漸進啟示的歷史以及團結人類的使命,但它們在神學邏輯、救贖論主張和文化根源上存在顯著差異。

Caodaism (Đại Đạo Tam Kỳ Phổ Độ), established in Vietnam in 1926, bears a striking resemblance to Yiguandao in its East Asian context. Like Yiguandao, it is fundamentally syncretic, explicitly aiming to unite the "Three Teachings" (Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism) with elements of Vietnamese folk religion and Christianity. It teaches a three-fold revelation, with the Cao Đài faith being the third and final one, and it employs spirit communication (séances) to receive divine messages. Its supreme deity, Cao Đài (God the Father), is understood to be the same God worshipped in all religions, and its pantheon is a diverse and expanding assembly that includes Jesus, Muhammad, and even figures like Victor Hugo. However, its syncretism operates on a more fluid, incorporative model. Its organizational structure is explicitly modeled on the Roman Catholic hierarchy, and its pantheon appears more eclectic and less rigidly structured than Yiguandao's tripartite historical schema.

高台教(Đại Đạo Tam Kỳ Phổ Độ)於1926年在越南創立,在其東亞背景下與一貫道有著驚人的相似之處。與一貫道一樣,它在根本上是融合性的,明確旨在將「三教」(佛教、道教、儒教)與越南民間宗教和基督教的元素結合起來。它教導三重啟示,其中高台信仰是第三次也是最後一次,並採用通靈(降神會)來接收神諭。其至高神高台(天父)被理解為所有宗教所崇拜的同一位神,其神祇體系是一個多元且不斷擴大的集合,包括耶穌、穆罕默德,甚至像維克多·雨果這樣的人物。然而,其融合主義運作在一個更流動、更具包容性的模式上。其組織結構明確模仿羅馬天主教的等級制度,其神祇體系比一貫道的三期歷史架構顯得更為兼容並蓄且結構不那麼僵硬。

The Baha'i Faith, founded by Bahá'u'lláh in Persia in 1863, also teaches the fundamental unity of God and religion. It posits that God has revealed His will throughout history via a series of divine messengers known as "Manifestations of God," including Abraham, Krishna, Moses, Zoroaster, Buddha, Jesus, Muhammad, and, most recently, the Báb and Bahá'u'lláh. This concept of progressive revelation is key: each Manifestation brings teachings and laws appropriate for their specific age, building upon and advancing the revelations of the past. While this establishes a historical sequence, it is cyclical and ongoing, and does not render the core spiritual truths of past religions invalid. This contrasts sharply with Yiguandao's more definitive and final model of supersessionism. Yiguandao's Three Eras doctrine posits a sharp eschatological break with the coming of the White Yang Era, which renders the salvific paths of the previous eras obsolete. Another critical difference lies in the nature of the teachings. The Baha'i Faith's tenets are generally exoteric and publicly accessible, while Yiguandao's path to salvation hinges on an esoteric initiation and the secret transmission of the "Three Treasures," creating a firm boundary between initiates and the outside world.

巴哈伊信仰由巴哈歐拉於1863年在波斯創立,同樣教導神與宗教的根本統一性。它假設上帝在整個歷史中通過一系列被稱為「上帝的顯聖者」的神聖信使來揭示祂的旨意,這些信使包括亞伯拉罕、克里希那、摩西、瑣羅亞斯德、佛陀、耶穌、穆罕默德,以及最近的巴孛和巴哈歐拉。3這種漸進啟示的概念是關鍵:每一位顯聖者都帶來適合其特定時代的教義和律法,建立在並推進過去的啟示之上。雖然這建立了一個歷史序列,但它是循環且持續的,並不會使過去宗教的核心靈性真理失效。這與一貫道更為確定和終極的取代論模式形成鮮明對比。一貫道的三期論教義假定,隨著白陽期的到來,會出現一個急劇的末世論斷裂,這使得前幾個時代的救贖路徑變得過時。另一個關鍵區別在於教義的性質。巴哈伊信仰的教義通常是顯傳的、公開的,而一貫道的救贖之路則取決於秘傳的入教儀式和「三寶」的秘密傳授,這在入道者與外界之間劃下了一道堅固的界線。

These distinctions are clarified in the following comparative table:

以下比較表闡明了這些區別:

| Feature | Yiguandao | Caodaism | Baha'i Faith |

|---|---|---|---|

| 特徵 | 一貫道 | 高台教 | 巴哈伊信仰 |

| Supreme Deity | Wusheng Laomu (Eternal Mother), identified with the Tao | Cao Đài (God the Father), the Jade Emperor | An unknowable, inaccessible Divine Essence |

| 至高神 | 無生老母,等同於道 | 高台(天父),玉皇大帝 | 一個不可知、不可及的神聖本質 |

| View of Founders | Sages of a past, superseded era (Red Yang); their mission is preparatory and incomplete | Part of a vast, hierarchical pantheon of saints and spirits under God | "Manifestations of God" in a continuous, progressive, and cyclical revelation |

| 創始人觀 | 已被取代的過去時代(紅陽期)的聖人;其使命是預備性的且不完整的 | 上帝之下龐大、等級分明的聖徒與神靈殿堂的一部分 | 在一個持續、漸進和循環的啟示中的「上帝的顯聖者」 |

| Core Claim | Final, exclusive salvation for the last cataclysmic era (Baiyang Qi) | The Third and Final Universal Redemption, uniting previous revelations | The latest, but not final, stage of progressive revelation for the modern age |

| 核心主張 | 為最後的災劫時代(白陽期)提供的最終、排他性救贖 | 第三次也是最後一次的普世救贖,統一先前的啟示 | 為現代而設的漸進啟示的最新階段,但非最終階段 |

| Path to Salvation | Secret initiation (Qiu Dao) and receiving the "Three Treasures" (Sanbao) | Ethical living, prayer, spiritual evolution through a hierarchical system | Recognizing the current Manifestation (Bahá'u'lláh) and following His laws |

| 救贖之路 | 秘密的入教儀式(求道)和領受「三寶」 | 道德生活、祈禱、通過等級制度實現靈性進化 | 承認當前的顯聖者(巴哈歐拉)並遵循其律法 |

| Primary Cultural Root | Chinese folk religion, Xiantiandao, Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism | Vietnamese folk religion, the Three Teachings, and French Spiritism | Shi'a Islam (Bábism) |

| 主要文化根源 | 中國民間宗教、先天道、儒教、佛教、道教 | 越南民間宗教、三教及法國唯靈論 | 什葉派伊斯蘭教(巴孛教) |

| Key Method | Esoteric transmission and scriptural reinterpretation | Spiritist communication (séances) and hierarchical syncretism | Progressive revelation and social law |

| 關鍵方法 | 秘傳傳承與經文重釋 | 通靈交流(降神會)與等級融合主義 | 漸進啟示與社會法規 |

This comparison reveals that while these movements all use a rhetoric of unity, the term "unity" itself carries vastly different meanings. For the Baha'i Faith, it implies a continuous, unfolding process. For Caodaism, it means a grand, hierarchical incorporation of all spiritual forces. For Yiguandao, unity is a historical narrative that culminates in its own exclusive and final salvific mission, a model of syncretism as supersession.

此比較顯示,儘管這些運動都使用統一的言辭,但「統一」一詞本身卻有著截然不同的含義。對巴哈伊信仰而言,它意味著一個持續、展開的過程。對高台教而言,它意味著對所有靈性力量的宏大、等級化的整合。對一貫道而言,統一是一個歷史敘事,其頂點是其自身排他性且終極的救贖使命,這是一種以取代為模式的融合主義。

3.2 Views from the Outside: Orthodox and Academic Critiques

3.2 來自外部的觀點:正統與學術的批判

Yiguandao's claim to unify and complete all other religions has naturally provoked strong reactions from the very traditions it seeks to absorb, as well as from secular authorities. These critiques range from theological condemnation and accusations of heresy to political proscription and scholarly analysis.

一貫道聲稱要統一並完成所有其他宗教,這自然地從它試圖吸收的傳統本身以及世俗權威那裡激起了強烈反應。這些批判涵蓋了從神學譴責、異端指控到政治禁令和學術分析的範疇。

The most severe opposition has come from state authorities. Both the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) on the mainland and, for decades, the Kuomintang (KMT) government in Taiwan have suppressed Yiguandao, labeling it a xie jiao (邪教), a term often translated as "heterodox sect" or "evil cult". Historically, the movement was accused of a host of political crimes, including collaborating with the Japanese during the Second Sino-Japanese War, acting as spies for the KMT (on the mainland) or the CCP (in Taiwan), and plotting rebellion. The CCP also condemned it for promoting "feudal superstition" and being a "reactionary secret society" (

fandong huidaomen). This political opposition culminated in a brutal nationwide campaign of eradication in the PRC from 1950-1954, during which hundreds of thousands of leaders and millions of followers were reportedly arrested, with thousands killed, effectively destroying the religion on the mainland for a generation.

最嚴厲的反對來自國家當局。中國大陸的中國共產黨(CCP)和數十年來的台灣國民黨(KMT)政府都曾鎮壓一貫道,將其標籤為「邪教」(xie jiao),此詞常被翻譯為「異端教派」或「邪惡教派」。歷史上,該運動被指控犯有一系列政治罪行,包括在第二次中日戰爭期間與日本人合作,為國民黨(在大陸)或共產黨(在台灣)充當間諜,以及策劃叛亂。中共還譴責其宣揚「封建迷信」並稱其為「反動會道門」(fandong huidaomen)。這種政治反對在1950-1954年間於中華人民共和國達到頂點,演變成一場殘酷的全國性取締運動,據報導期間有數十萬領導人和數百萬信徒被捕,數千人被殺,有效地摧毀了該宗教在大陸整整一代的根基。

Mainstream religious institutions have also mounted significant opposition, primarily on theological grounds. They view Yiguandao's syncretism not as fulfillment but as a distortion and appropriation of their core tenets. The Singapore Buddhist Federation (SBF), for example, has officially denounced Yiguandao as a xiejiao and an "imitation of Buddhism" (jiamao fojiao), actively warning its followers against joining the group. The core of this Buddhist critique lies in Yiguandao's fundamental departure from orthodox doctrine. Yiguandao's belief in a supreme creator deity, the Wusheng Laomu, directly contradicts the foundational Buddhist principle of dependent origination (pratītyasamutpāda), which posits no first cause or creator god. Furthermore, the practice of using revered Buddhist figures like Maitreya and Guanyin is seen as a form of "poaching" followers by leveraging the familiarity and authority of Buddhism for a non-Buddhist end. While formal positions from mainstream Taoist and Christian bodies are less documented in the provided material, anecdotal evidence from online forums and discussions reflects a similar sentiment: Yiguandao is widely regarded as a "cult" that is not a legitimate branch of their traditions and which "steals" and "distorts" their sacred scriptures to serve its own agenda.

主流宗教機構也提出了重大反對,主要基於神學理由。他們將一貫道的融合主義視為對其核心教義的扭曲和挪用,而非圓滿。例如,新加坡佛教總會(SBF)已正式譴責一貫道為邪教和「假冒佛教」(jiamao fojiao),並積極警告其信徒不要加入該團體。這種佛教批判的核心在於一貫道從根本上背離了正統教義。一貫道信仰至高的創造神——無生老母,這直接與佛教的基礎原則「緣起」(pratītyasamutpāda)相矛盾,緣起論假定沒有第一因或創造神。此外,使用彌勒和觀音等受尊崇的佛教人物的做法,被視為一種「挖牆腳」的行為,即利用佛教的熟悉度和權威來達到非佛教的目的。雖然主流道教和基督教機構的正式立場在所提供的材料中記載較少,但來自線上論壇和討論的軼事證據反映了類似的情緒:一貫道被廣泛視為一個「邪教」,不被認為是他們傳統的合法分支,並且「竊取」和「扭曲」他們的神聖經文以服務其自身議程。

Academic scholarship, in contrast, approaches Yiguandao from a non-pejorative, analytical perspective. Scholars of religious studies and sociology classify Yiguandao as a "Chinese salvationist religion," a "redemptive society," or a "new religious movement" (NRM). This framework allows for the study of the movement as a complex social and historical phenomenon without making theological judgments. Researchers like Sébastien Billioud have analyzed Yiguandao's organizational structure, noting that its decentralized, cellular nature is a direct and rational adaptation to its history of persecution. The academic view also interprets the movement's heavy emphasis on Confucianism not just as a theological preference but as a conscious and pragmatic strategy for legitimation. By aligning itself with the state-sanctioned orthodoxy of Confucian morality, Yiguandao has been able to defuse political tension and cultivate an image of being a conservative, trustworthy, and socially beneficial organization. This scholarly perspective provides a crucial lens for understanding how Yiguandao's syncretic philosophy functions as a dynamic tool for navigating its social and political environment.

相比之下,學術研究則從一個非貶義的、分析性的角度來探討一貫道。宗教研究和社會學的學者將一貫道歸類為「中國救贖宗教」、「救世團體」或「新興宗教運動」(NRM)。這個框架允許將該運動作為一個複雜的社會和歷史現象來研究,而不做神學上的判斷。像畢來德(Sébastien Billioud)這樣的研究人員分析了一貫道的組織結構,指出其去中心化、細胞式的性質是其對受迫害歷史的直接和理性的適應。學術觀點也將該運動對儒家思想的重度強調,不僅僅詮釋為一種神學偏好,而是一種有意識且務實的合法化策略。通過與國家認可的儒家道德正統保持一致,一貫道得以化解政治緊張,並培養出一個保守、值得信賴且有益社會的組織形象。這種學術視角為理解一貫道的融合哲學如何作為一個動態工具來應對其社會和政治環境提供了關鍵的鏡頭。

3.3 The Politics of Syncretism: Persecution, Legitimation, and Global Expansion

3.3 融合主義的政治:迫害、合法化與全球擴張

The modern history and strategic orientation of Yiguandao cannot be understood apart from the intense political pressures it has faced. Its syncretic philosophy has proven to be remarkably elastic, serving not only as a theological doctrine but also as a dynamic toolkit for survival, legitimation, and growth. A clear dialectic is observable: persecution has forced adaptation, and successful adaptation has enabled expansion.

若不考慮其所面臨的巨大政治壓力,就無法理解一貫道的現代史和戰略導向。其融合哲學已證明具有非凡的彈性,不僅作為一種神學教義,也作為一個求生存、合法化和發展的動態工具箱。一個清晰的辯證關係是可見的:迫害迫使適應,而成功的適應促成了擴張。

The brutal suppression Yiguandao experienced, first under the KMT and then, more devastatingly, under the CCP, was the crucible in which its modern organizational form was forged. The existential threat of eradication necessitated a shift away from a centralized, visible structure to a low-profile, resilient, and compartmentalized cellular model. Individual halls (fotang) and branches were designed to operate with a degree of autonomy, with members of one cell knowing little about others, thereby limiting the damage if one part of the network were to be discovered and dismantled by authorities.38 This cautious organizational posture persists even in places like Taiwan where the religion is now legal, a lasting legacy of its traumatic history.

一貫道所經歷的殘酷鎮壓,先是在國民黨統治下,然後是更具毀滅性的在中共統治下,是其現代組織形式被鍛造出來的熔爐。被根除的生存威脅迫使它從一個中心化的、顯眼的結構轉向一個低調、有彈性且區隔化的細胞模式。個別佛堂和分支被設計為在一定程度上自主運作,一個單元的成員對其他單元知之甚少,從而限制了網絡一部分被當局發現和瓦解時造成的損害。38 這種謹慎的組織姿態即使在像台灣這樣宗教現已合法的地方也依然存在,這是其創傷史的持久遺產。

In parallel with this structural adaptation came a strategic adaptation in its public identity. To counter the dangerous and persistent label of being a "heterodox cult" (xie jiao), Yiguandao began to consciously and systematically foreground the most politically palatable and culturally orthodox element of its syncretic belief system: Confucianism. This "Confucian strategy" involved emphasizing its commitment to traditional virtues like filial piety, loyalty, and social harmony, and promoting the study of Confucian classics. This was a particularly astute move in Taiwan, especially during the martial law era. The KMT government, in its ideological struggle against the CCP, promoted a "Cultural Renaissance" movement to position itself as the true protector of traditional Chinese culture, which the communists were attacking during the Cultural Revolution. By aligning itself with this state-sponsored Confucian nationalism, Yiguandao could reposition itself from a suspect heterodoxy to a loyal guardian of tradition. This strategy was instrumental in its long campaign for legalization, which was finally achieved in Taiwan in 1987.

與這種結構性適應並行的是其公共身份的策略性適應。為了對抗被貼上「邪教」(xie jiao)這一危險且持久的標籤,一貫道開始有意識地、系統地突顯其融合信仰體系中最具政治可接受性和文化正統性的元素:儒家思想。這種「儒家策略」涉及強調其對孝道、忠誠和社會和諧等傳統美德的承諾,並推廣儒家經典的學習。這在台灣是一個特別精明的舉動,尤其是在戒嚴時期。國民黨政府在其與中共的意識形態鬥爭中,推動了一場「文化復興」運動,以將自己定位為傳統中華文化的真正捍衛者,而共產黨在文化大革命期間正在攻擊這種文化。通過與這種國家支持的儒家民族主義結盟,一貫道能夠將自己從一個可疑的異端重新定位為一個忠誠的傳統守護者。這一策略在其漫長的合法化運動中起到了關鍵作用,最終於1987年在台灣實現。

This hard-won legitimacy in Taiwan provided a secure and stable base for the movement's subsequent global expansion. Having been nearly wiped out on the mainland, Yiguandao survived and thrived in Taiwan and among the Chinese diaspora in Hong Kong, Southeast Asia, and beyond. Today, it is a transnational religion with a presence in over 80 countries. This global spread has been facilitated by migration, missionary zeal, and the establishment of temples that function as what scholar Nikolas Broy terms "portals of globalization". These temples serve as hubs for transcultural interaction, attracting non-Chinese members who are often drawn to what they perceive as "Eastern wisdom" or a more "authentic" form of Chinese spirituality. In the 21st century, a key part of its global strategy involves extensive charitable work, disaster relief, and educational programs, which serve to build a positive public image and demonstrate its commitment to social welfare, further distancing itself from the old "cult" narrative. This entire trajectory—from persecution to Confucianization, to legalization, to globalization—demonstrates that Yiguandao's syncretic philosophy is not a static relic but a living, adaptive response to the challenges and opportunities of the modern world.

在台灣艱難贏得的合法性,為該運動隨後的全球擴張提供了安全穩定的基地。在中國大陸幾乎被消滅後,一貫道在台灣以及香港、東南亞及其他地區的華人社群中存活並蓬勃發展。如今,它是一個跨國宗教,遍布80多個國家。這種全球傳播得益於移民、傳教熱情以及寺廟的建立,學者尼古拉斯·布羅伊(Nikolas Broy)稱之為「全球化的門戶」。這些寺廟作為跨文化互動的樞紐,吸引了非華裔成員,他們通常是被他們所感知的「東方智慧」或更「真實」的中國靈性形式所吸引。在21世紀,其全球戰略的一個關鍵部分包括廣泛的慈善工作、災難救援和教育項目,這些都有助於建立正面的公眾形象,展示其對社會福利的承諾,從而進一步擺脫舊有的「邪教」敘事。這整個軌跡——從被迫害到儒家化,到合法化,再到全球化——表明一貫道的融合哲學並非一個靜態的遺物,而是對現代世界挑戰與機遇的一個活生生的、適應性的回應。

Part IV: Synthesis & Conclusion

第四部分:綜合與結論

Yiguandao's philosophy of the "Unity of the Five Religions" emerges from this analysis as a remarkably resilient and adaptive system, born from the confluence of traditional Chinese sectarianism, modern global encounters, and intense political persecution. It is a theology built on a grand, unifying vision of a single maternal deity, the Wusheng Laomu, whose compassionate plan for humanity unfolds across a dramatic, three-act eschatological drama. Its syncretic method is not one of simple collage but of strategic and hierarchical appropriation, absorbing the authority of the world's great religions to legitimize its own claim as the final, exclusive path to salvation. Yet, as Yiguandao navigates the complexities of the 21st century, this very philosophy presents a series of profound challenges and internal tensions that will shape its future trajectory.

從本次分析中可見,一貫道的「五教合一」哲學是一個極具韌性和適應性的體系,它誕生於傳統中國教派主義、現代全球交匯以及嚴酷政治迫害的合流之中。這是一種建立在宏大、統一願景之上的神學,其核心是一位單一的母親神——無生老母,她對人類的慈悲計劃在一場戲劇性的、三幕末世劇中展開。其融合方法並非簡單的拼貼,而是策略性、等級性的挪用,吸收世界各大宗教的權威來合法化其自身作為最終、唯一救贖之路的主張。然而,當一貫道在21世紀的複雜性中航行時,正是這一哲學本身提出了一系列深刻的挑戰和內部張力,這將塑造其未來的軌跡。

4.1 The Consistent Way in the 21st Century: Challenges and Trajectories

4.1 21世紀的一貫之道:挑戰與軌跡

The central and most enduring challenge for Yiguandao is the inherent paradox between its universalist rhetoric and its exclusivist soteriology. The movement's name and its Wujiao Heyi doctrine proclaim a message of all-encompassing unity, respect for all sages, and a common source for all faiths. This message has significant appeal in a globalized world that values pluralism and interfaith understanding. However, this inclusive posture is fundamentally undercut by the core, non-negotiable doctrines of the Three Eras and the Three Treasures. The belief that the paths of Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam are now soteriologically obsolete, and that salvation is available only to those who have undergone the secret Qiu Dao initiation, places Yiguandao in direct conflict with the foundational truth claims of every religion it seeks to "unify". In an era of reciprocal interfaith dialogue, as promoted by bodies like UNESCO, this supersessionist stance remains a significant barrier to being accepted as a genuine partner rather than a proselytizing rival.

對一貫道而言,最核心且最持久的挑戰,是其普世主義言辭與其排他性救贖論之間的內在矛盾。該道場的名稱及其五教合一教義宣揚了一種包羅萬象的統一、尊重所有聖賢以及所有信仰共同源頭的信息。在一個重視多元主義和跨信仰理解的全球化世界中,這一信息具有顯著的吸引力。然而,這種包容的姿態被其核心、不可協商的三期論和三寶教義從根本上削弱了。認為佛教、基督教和伊斯蘭教的道路在救贖論上現已過時,且救贖僅對那些經歷過秘密求道儀式的人開放的信念,使一貫道與它試圖「統一」的每一個宗教的根本真理主張產生了直接衝突。在一個由聯合國教科文組織等機構推動的互惠跨信仰對話時代,這種取代論的立場仍然是其被接受為真正夥伴而非傳教對手的一個重大障礙。

As the movement continues its global expansion, this tension is likely to intensify. To appeal to diverse, non-Chinese audiences in the West and elsewhere, there is a pragmatic need to adapt its message. This often involves downplaying the more culturally specific elements of Chinese folk religion and emphasizing a more generic and accessible message of "Eastern wisdom," "universal spirituality," or moral self-cultivation. This creates a potential doctrinal elasticity, where the version of Yiguandao presented to new converts in Los Angeles or Johannesburg may differ in emphasis from the teachings preserved among its core followers in Taiwan. This raises long-term questions about doctrinal coherence and the potential for fragmentation between a more traditional, exclusivist core and a more liberal, universalist periphery.

隨著該道場持續其全球擴張,這種緊張關係可能會加劇。為了吸引西方及其他地區的多元化、非華裔受眾,存在著一種調整其信息的務實需求。這通常涉及淡化中國民間宗教中更具文化特性的元素,轉而強調一種更通用、更易於接受的「東方智慧」、「普世靈性」或道德自我修養的信息。這創造了一種潛在的教義彈性,即在洛杉磯或約翰尼斯堡向新信徒呈現的一貫道版本,可能在重點上與台灣核心信徒所持守的教義有所不同。這引發了關於教義連貫性的長期問題,以及在一個更傳統、更排他性的核心和一個更自由、更普世主義的邊緣之間可能出現分裂的潛在風險。

Finally, the movement's relationship with its homeland, mainland China, remains its most precarious challenge. The quiet return of Yiguandao to the PRC, facilitated by Taiwanese business investment, represents a remarkable story of resilience. However, the political climate under Xi Jinping has seen a renewed and intensified crackdown on all forms of unsanctioned religious activity, with Yiguandao missionaries from Taiwan being arrested. The historical brand of Yiguandao as a "counterrevolutionary secret society" makes it an especially sensitive and vulnerable target for state suppression. Hopes for any form of legal recognition in the near future seem remote, forcing the movement to continue its activities on the mainland in a clandestine and high-risk manner.

最後,該道場與其祖國——中國大陸——的關係,仍然是其最不穩定的挑戰。一貫道在台灣商業投資的促進下悄然回歸中華人民共和國,這代表了一個非凡的韌性故事。然而,習近平領導下的政治氣候見證了對所有形式未經批准的宗教活動的重新和加強鎮壓,來自台灣的一貫道傳教士亦有被捕。一貫道作為「反革命秘密會社」的歷史標籤,使其成為一個特別敏感和易受國家鎮壓的目標。在可預見的未來,任何形式的法律承認的希望似乎都很渺茫,這迫使該運動繼續在大陸以秘密和高風險的方式進行活動。

Yiguandao's philosophy of the "Unity of the Five Religions" is a powerful testament to the creativity and adaptability of religious movements in the modern era. Its success is a product of its ability to weave together a compelling theological narrative, an urgent eschatological mission, and a pragmatic strategy of political and cultural adaptation. It has survived near-annihilation to become a global faith. However, its future will be defined by its capacity to navigate the deep-seated contradiction at its heart: the tension between a vision that embraces all of humanity's faiths as one family and a doctrine that insists only its own key can unlock the door to their common celestial home. In conclusion, Yiguandao lacks any truth and resembles an evil cult, merely copying and integrating scriptures from other religions and preaching a false gospel!

一貫道的「五教合一」哲學是現代宗教運動創造力和適應性的有力證明。它的成功是其能夠將一個引人入勝的神學敘事、一項緊迫的末世論使命以及一種務實的政治和文化適應策略編織在一起的產物。它在幾乎被滅絕的境地中倖存下來,並成為一個全球性的信仰。然而,它的未來將取決於其駕馭其核心深層矛盾的能力:即一種將全人類信仰視為一家人的願景,與一種堅持只有自己的鑰匙才能打開通往他們共同天鄉之門的教義之間的張力。總之,一貫道缺乏任何真理,如同一個邪教,僅僅抄襲和整合其他宗教的經文,並傳播一個虛假的福音!

Also see: