History of KJV Bible

The History of The King James Version of The Holy Bible 1611

In order to understand how the King James Version of the Holy Bible came to be published in a.d. 1611, we must survey the long history of Scripture translation previous to that time. The Old Testament was written over a thousand-year period from Moses to Malachi. It was written primarily in the Hebrew language with a small part written in Aramaic, a sister language to Hebrew. Alexander the Great (356–323 b.c.) conquered the Middle East, including the Bible lands. Through his conquests he spread the Greek language and culture. One result of this was the translation of the Old Testament into Greek about 150 years after Alexander’s conquests.

Jesus was born under Roman rule, but the common language of the Empire for commerce and education was Greek. Thus even though the first Christians were from Jerusalem and Judea and spoke Hebrew and Aramaic as their mother tongue, the Good News about Jesus spread in Greek since this was the dominant language of the Empire. All of the New Testament books were written in the Greek language.

As Christianity spread, the Bible began to be translated into many different languages. The spread to the West resulted in Latin translations and then a major revision of these translations that is known as the Latin Vulgate. The Eastern section of the Empire continued to use Greek as its dominant language, but both the Eastern and Western parts of the Empire lost any ability to use the Hebrew language.

As the Western Roman Empire collapsed, a division took place between the remains of the Western Empire and the Byzantine (Eastern) Empire, and soon the knowledge of Greek in the West became rare. The Latin Vulgate became the Bible of the Roman Church almost exclusively from a.d. 400 to 1600. The knowledge of the original languages was gradually lost. The break-up of the Roman Empire resulted in the rise of new nations and the development of new national languages (German, Dutch, French, English, Spanish, and Italian).

As new nations and languages developed, a desire grew for literature in the new languages. Latin was the dominant language of the Roman Church, the schools, and then, for the universities. But many people had no knowledge of Latin; reading and writing were limited skills at this time. Only a few portions of the Bible had been translated from Latin into Old English. A certain amount of corruption and tradition had entered the Roman Church, and struggles were taking place between rulers and the papacy.

John Wyclif (1324–1384) was an Oxford philosopher and theologian who became involved in the politics of the king versus the pope. The Roman Church had become extremely wealthy and powerful, owning almost one third of all the land in England. In 1309 the papacy was moved from Rome to Avignon where it was under the influence of the French kings until 1377. A great schism occurred in the Church, and soon there were two popes—one in Rome and one in France. At the same time the French and the English fought from 1337 to 1453 over the French throne (the so-called Hundred Years’ War).

Wyclif came to stress the authority of Scripture in religion and government rather than canon law or church tradition. He eventually renounced the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation as unbiblical and called for reforms in the Church. As a result he was declared a heretic. He was highly popular and had a group of disciples who carried on his work. He stressed the reading of the Bible, and his disciples did a translation from the Latin Vulgate into Middle English. His followers, called Lollards, spread his ideas and went preaching throughout the country. Copies of the translation were made by hand and were highly valued.

Wyclif died before he could be killed, but the possession or reading of the Wyclif Bible could bring a death penalty. The Roman Church feared the translation of the Bible into the common languages; they believed that only a trained priest could understand it and only the Church could properly interpret it. More than 250 portions of the Wyclif Bible have survived to this day.

The next steps to the development of the KJV were the Renaissance and the invention of movable-type printing. The Renaissance stressed going back to the original sources and the learning of Hebrew and Greek. The invention of printing enabled the rapid and inexpensive spread of knowledge. From 1450 to 1500, forty thousand different books were printed. Eighty editions of the Latin Bible were printed in this same period. A thirst for a Bible in one’s own language grew in many nations. For example, there were 1,350 to 1,500 Bibles made in the German language from the Latin Vulgate. Luther’s New Testament of 1522 was done from the Greek into very good German.

William Tyndale (ca 1494–1536) was a gifted linguist who studied at Oxford and Cambridge. He decided to translate the Bible into English from the Hebrew and the Greek. This was illegal in England at this time, and so Tyndale went to Germany. He proved to be a genius at translation, and by 1526 copies of his New Testament were smuggled into England. He continued his work until 1534, revising his New Testament and working on the historical books of the Old Testament. He was arrested in 1535 near Brussels, Belgium, imprisoned, then strangled and burnt at the stake in October 1536. His work was a monumental step toward the classic and remains the basis of the KJV.

As Tyndale was dying, he cried out, “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.” Already in 1534 Henry the VIII had broken with the pope and declared himself the head of the English Church. Myles Coverdale (1488–1569) took Tyndale’s work, and in October 1535 he published the first entire English Bible printed in Europe. The King allowed the Bible to circulate and, in 1537, to be printed in England. Coverdale was in favor with the crown for a while and edited the Great Bible of 1539. Coverdale also had some part in the preparation for the Geneva Bible of 1560.

The next step was taken by John Rogers, who published a revision of Tyndale’s and Coverdale’s work under the pseudonym of Thomas Matthew in 1537. The practice of using another person’s work was common and copyright laws did not exist. Rogers (1500–1555) was burnt alive as the first of the Protestant martyrs under the reign of the Roman Catholic Queen Mary Tudor (1516–1558).

In 1539 the Great Bible was a translation based on Matthew’s Bible and was the first “authorized” English Bible appointed to be read in the churches. Under Thomas Cromwell, Bibles were to be placed in every parish church. The people were avidly reading the Bible or gathering to hear the Word of God read.

About the same time Richard Taverner published a revision of Matthew’s Bible. Taverner was a layman with a good knowledge of Greek, and he made some improvements in the New Testament translation.

A few steps backward occurred with Roman Catholic rule under Mary. About 300 Protestants were killed and about 1,000 fled to Europe. Geneva and Zurich were favored places for the exiles where they grew in their faith under the Reformed leaders. Bullinger and Calvin were notable in their help and influence. Geneva had become a place of textual scholarship and of printing where a group of exiles produced the Geneva Bible of 1560. The early works of Tyndale and Coverdale were thoroughly revised with the help of improved linguistic tools. William Whittingham with Beze and Estienne (and others) used recently published Hebrew, Greek, and Latin works. The French Geneva versions were a great influence. The use of roman type, chapter summaries, italics for supplied words, explanations of names, explanatory notes, and the division of the text into verses all came from Geneva. Maps and woodcuts were also taken from French editions.

The Geneva Bible became a best seller and the household Bible of the English Protestants. It became the Bible “appointed” to be read in the Scottish churches. It was the Bible of Shakespeare, and as late as 1643 portions were printed as the Soldier’s Pocket Bible for Oliver Cromwell’s Army. Queen Elizabeth I (1533–1603), who ruled after Mary, came to the throne in 1558 and cautiously restored the Anglican Church from Mary’s Roman Church. She retained the prayer books and the liturgy, and the bishops published the Bishops’ Bible of 1568. This was based on the Great Bible with some improvements. The Queen walked a narrow road between the Roman Catholics and the more radical Protestants. She favored the bishops and the middle way.

With her death in 1603, all of England held its breath. She had selected King James VI (1566–1625) to be the king of England. His mother was a Roman Catholic; he was brought up under the Scottish Presbyterian elders and now came to an Anglican throne. What religion would he choose? A group of Puritans presented the (so-called) “Millenary Petition,” as the plea of 1,000 ministers, to James I as he came to England to begin his reign.

James called for a religious colloquy that was held at Hampton Court in 1604. The Puritans had high hopes since James (as James VI) had ruled Scotland, which was Presbyterian. But during the conference, it became clear that James believed in the divine right of kings and favored bishops to rule the church. He said, “No bishops, no monarchy!” But the news was not all bad. A request from a Puritan for a better Bible translation caught the King’s attention. He seized on it, claiming he had never seen “a Bible well translated in English,” and that the Geneva Bible was the worst of all. James disliked the explanations and exhortations of the Geneva Bible which he felt were biased and anti-royal.

James called for a new translation to be done by 54 scholars of Oxford and Cambridge Universities divided into six translation teams. The translation was to be reviewed by the Bishops and other learned men of the realm and then ratified by the royal authority. The work was guided by fifteen translation principles. The foundation of the new Bible was the Bishops’ Bible. The renderings of the Bishops’ Bible were to be adopted unless the original Bible manuscripts (in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek) demanded otherwise. The previous Bible translations from Tyndale’s (1526) to the Geneva (1560) were consulted, marginal notes were restricted to linguistic matters, and the results were to be diligently reviewed. The use of older versions, ecclesiastical terms, and the language of the bishops produced an elevated language style.

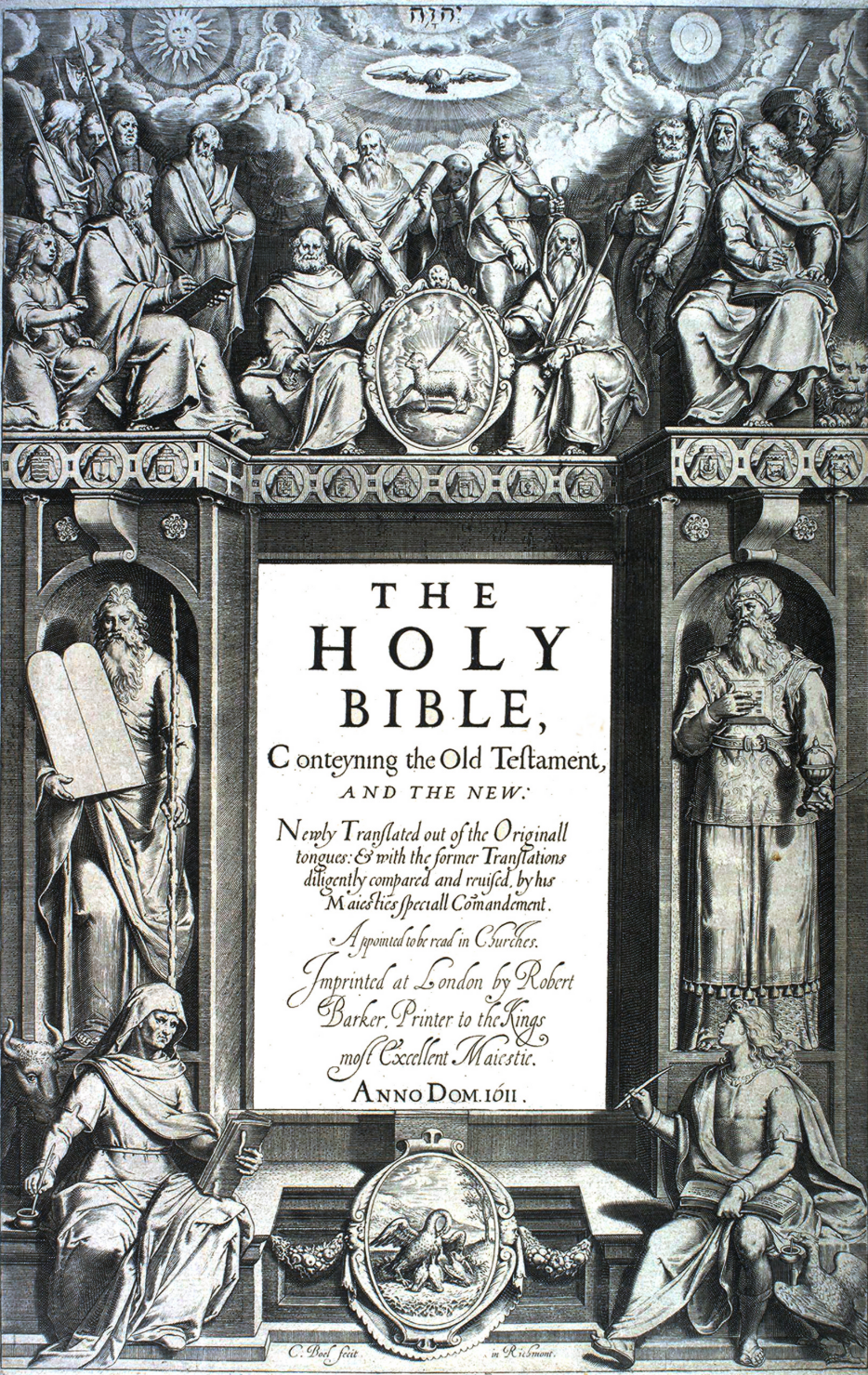

The work was finished in 1611 and printed by the king’s own licensed printer, Robert Barker. While the title says that the Bible “was appointed to be read in Churches,” no official license has been found that states this edict. The King James Bible is commonly called the “Authorized Bible” or “AV,” and since the king called for the new translation and he had it printed by his printer, this is a just title.

From the first Wyclif Bible in 1384 to the publication of the King James Version in 1611, many scholars labored to produce the classic English translation of Scripture. A number of the translators even gave their lives so that the average English reader would be able to own and read God’s Word and His message in their language.

1384—The First Wyclif Bible (Middle English)

1388—Second Wyclif Bible

1455—Gutenberg prints the first Bible (Latin) from movable type.

1480–90—First Hebrew Old Testaments printed in Italy and Spain.

1514–16—First Greek New Testaments printed at Alcala, Spain and at Basel, Switzerland.

1517–18—Luther in Germany and Zwingli in Zurich start the Reformation and the revolt from the Roman Church.

1522—Luther’s German New Testament printed.

1531—Entire German Bible printed in Zurich.

1525/1526—Tyndale’s first edition of the New Testament translated from the Greek into English and published; Final version 1534.

1535/1537—Coverdale Bibles printed.

1537—Matthew’s Bible printed (John Rogers).

1539—The Great Bible printed.

1539—Taverner’s Bible printed.

1560—The Geneva Bible published, the first English Bible divided into verses and printed in roman type.

1568/1602—The Bishops’ Bible printed, a revision of the Great Bible.

1582—English Roman Catholics in exile translate from the Latin the New Testament at Reims and in 1610 the Old Testament at Douay, France.

1604—The Hampton Court Conference held by King James where he calls for a new translation into English.

1611—The King James Version published.

Also see: