Glory Vs Cross-Two Theologies

The Theology of Glory Versus The Theology of The Cross: A Fundamentalist Examination

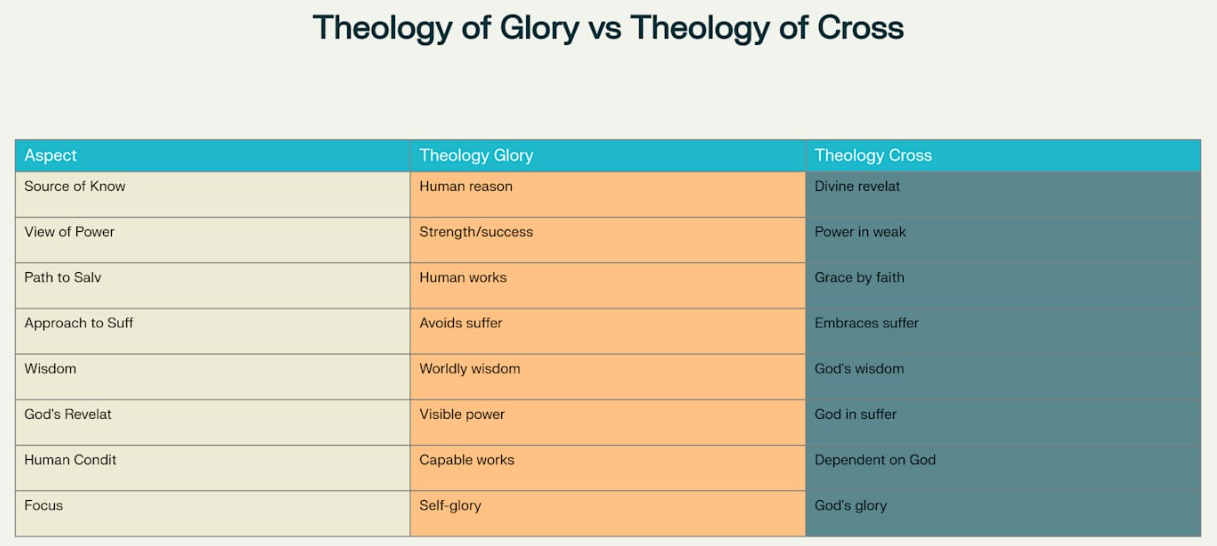

The distinction between the Theology of Glory (theologia gloriae) and the Theology of the Cross (theologia crucis) represents one of the most profound theological divides in Christian understanding, fundamentally shaping how believers comprehend God's revelation, salvation, and the Christian life. This examination, grounded firmly in the King James Version (KJV) of Scripture, explores these contrasting theological frameworks through the lens of orthodox, fundamentalist interpretation.

Historical Origins & The Heidelberg Disputation

The formal articulation of these theological concepts emerged from Martin Luther's Heidelberg Disputation of April 26, 1518, where he presented twenty-eight theses that would revolutionize theological understanding. In this disputation, Luther specifically contrasted these two approaches in theses 19-21, establishing a framework that continues to influence theological discourse today.

Thesis 19 declares: "That person does not deserve to be called a theologian who looks upon the invisible things of God as though they were clearly perceptible in those things which have actually happened". Thesis 20 counters: "He deserves to be called a theologian, however, who comprehends the visible and manifest things of God seen through suffering and the cross". Thesis 21 provides the crucial distinction: "A theologian of glory calls evil good and good evil. A theologian of the cross calls the thing what it actually is".

This disputation emerged from Luther's growing conviction that medieval scholasticism, heavily influenced by Aristotelian philosophy, had corrupted biblical theology by elevating human reason above divine revelation. The scholastic tradition sought to harmonize faith with natural reason, particularly through the systematic theology of Thomas Aquinas, who had integrated Aristotelian methodology into Christian doctrine.

Biblical Foundations of The Theology of The Cross

The Scriptures provide abundant testimony to the centrality of the cross in God's redemptive plan, establishing the theological foundation that Luther would later systematize. The KJV preserves the precision of these foundational truths with particular clarity.

Old Testament Prophecies

The prophet Isaiah provides the most comprehensive Old Testament foundation for understanding God's method of revelation through suffering. Isaiah 53:3-5 declares: "He is despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief: and we hid as it were our faces from him; he was despised, and we esteemed him not. Surely he hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows: yet we did esteem him stricken, smitten of God, and afflicted. But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities: the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed".

This prophetic passage reveals several crucial elements that establish the theology of the cross: first, God's chosen method of revelation through apparent weakness and suffering; second, the vicarious nature of Christ's sufferings for human sin; third, the world's inability to recognize God's power in apparent weakness; and fourth, the healing and peace that come through divine weakness rather than human strength.

The Scripture provides extensive cross-references demonstrating that Isaiah 53 finds its ultimate fulfillment in the New Testament accounts of Christ's crucifixion, particularly in Matthew 8:17, Galatians 3:13, Hebrews 9:28, and 1 Peter 2:24.

New Testament Fulfillment

The Apostle Paul's writings provide the most systematic New Testament development of the theology of the cross. 1 Corinthians 1:18 establishes the fundamental principle: "For the preaching of the cross is to them that perish foolishness; but unto us which are saved it is the power of God". This verse reveals the divine paradox that God's power is manifested in what appears to be weakness and foolishness to unregenerate human reason.

Paul expands this principle in 1 Corinthians 1:21-25: "For after that in the wisdom of God the world by wisdom knew not God, it pleased God by the foolishness of preaching to save them that believe. For the Jews require a sign, and the Greeks seek after wisdom: But we preach Christ crucified, unto the Jews a stumbling block, and unto the Greeks foolishness; But unto them which are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God, and the wisdom of God. Because the foolishness of God is wiser than men; and the weakness of God is stronger than men".

This passage reveals that human wisdom, whether Jewish demand for miraculous signs or Greek philosophical speculation, cannot apprehend God's truth. Instead, God has chosen the apparent "foolishness" of the cross as His method of revelation and redemption.

Fundamental Distinctions Between The Two Theologies

The theology of glory and the theology of the cross represent fundamentally different approaches to understanding God, salvation, and Christian living. These distinctions extend far beyond mere theological preference to encompass entirely different worldviews.

Source of Knowledge & Revelation

The theology of glory seeks to know God through natural revelation, human reason, and philosophical speculation. It assumes that the "invisible things of God" can be "clearly perceived" through creation and human works. This approach, exemplified in medieval scholasticism, attempts to construct knowledge of God through Aristotelian logical categories and natural theology.

In contrast, the theology of the cross insists that God can only be truly known through His self-revelation in the crucified Christ. As Luther emphasized, this knowledge comes "through suffering and the cross," not through human speculation or natural revelation. 1 Corinthians 2:2 exemplifies this principle: "For I determined not to know any thing among you, save Jesus Christ, and him crucified".

View of Human Nature & Capability

The theology of glory maintains an optimistic view of human capability after the Fall, believing that humans retain some ability to cooperate with God's grace and contribute to their salvation. This perspective underlies the prosperity gospel movement, which teaches that faith, positive thinking, and material giving will result in health, wealth, and success.

The theology of the cross, grounded in Scripture, recognizes the total depravity of human nature and complete dependence on God's grace. Romans 7:18 declares: "For I know that in me (that is, in my flesh,) dwelleth no good thing." The Heidelberg Disputation's Thesis 13 states: "Free will, after the fall, exists in name only, and as long as it does what it is able to do, it commits a mortal sin".

Approach To Suffering & Weakness

Perhaps no distinction is more crucial than each theology's approach to suffering. The theology of glory seeks to avoid, minimize, or quickly overcome suffering, viewing it as a sign of insufficient faith or divine disfavor. This perspective underlies much contemporary "health and wealth" preaching.

The theology of the cross, however, recognizes suffering as God's chosen method of revealing His power and accomplishing His purposes. 2 Corinthians 13:4 declares: "For though he was crucified through weakness, yet he liveth by the power of God. For we also are weak in him, but we shall live with him by the power of God toward you".

Detailed Theological Analysis of Key Passages

1 Corinthians 1:18-25: The Central Text

This passage serves as the theological foundation for understanding the theology of the cross. The Greek word translated "foolishness" (moria) in the KJV carries the connotation of complete absurdity or senselessness to human reason. Paul deliberately chooses this strong language to emphasize the radical disconnect between divine and human wisdom.

The phrase "power of God" (dunamis theou) indicates not merely divine strength but God's effective working in salvation. The cross becomes the means by which God's power operates, not despite its apparent weakness, but through that weakness.

1 Corinthians 1:21 reveals God's sovereign choice to save through "the foolishness of preaching" rather than through human wisdom or philosophical demonstration. The word "pleased" (eudokesen) indicates God's deliberate, sovereign decision to employ this method.

1 Corinthians 1:22-23 identify the two primary forms of theology of glory: Jewish demand for miraculous signs and Greek pursuit of philosophical wisdom. Both represent attempts to know God on human terms rather than accepting His self-revelation in the cross.

Isaiah 53: The Suffering Servant Prophecy

Isaiah 53 provides the Old Testament foundation for understanding God's method of revelation through suffering. The chapter begins with the question "Who hath believed our report?" indicating that this revelation would be difficult for human reason to accept.

Isaiah 53:2 describes the Messiah's humble appearance: "he hath no form nor comeliness; and when we see him, there is no beauty that we should desire him." This emphasizes that God's revelation comes through apparent insignificance rather than impressive display.

Isaiah 53:5 provides the theological center: "But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities: the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed." This establishes the substitutionary nature of Christ's sufferings and the vicarious atonement that forms the heart of the theology of the cross.

2 Corinthians 13:4: Power Through Weakness

This verse encapsulates the paradox of the theology of the cross: "For though he was crucified through weakness, yet he liveth by the power of God." The Greek construction emphasizes that Christ's crucifixion was accomplished through (dia) weakness, not despite it.

The phrase "liveth by the power of God" indicates that Christ's resurrection demonstrates how God's power operates through apparent weakness rather than in spite of it. This becomes the pattern for Christian living: "For we also are weak in him, but we shall live with him by the power of God toward you".

Contemporary Applications & Implications

Critique of Prosperity Theology

The theology of the cross provides a biblical foundation for critiquing contemporary prosperity theology, which represents a modern manifestation of the theology of glory. Prosperity teaching emphasizes health, wealth, and success as indicators of God's blessing and proper faith.

However, this approach contradicts the clear biblical pattern established in both Old and New Testaments. Hebrews 11:36-38 describes faithful servants who "had trial of cruel mockings and scourgings, yea, moreover of bonds and imprisonment: They were stoned, they were sawn asunder, were tempted, were slain with the sword: they wandered about in sheepskins and goatskins; being destitute, afflicted, tormented; (Of whom the world was not worthy)."

Understanding Spiritual Maturity

The theology of the cross redefines spiritual maturity not as the absence of suffering or the presence of material blessing, but as conformity to Christ in His sufferings. Philippians 3:10 expresses Paul's desire: "That I may know him, and the power of his resurrection, and the fellowship of his sufferings, being made conformable unto his death."

This understanding stands in direct opposition to theologies that measure spiritual progress by external prosperity or freedom from difficulty. Instead, spiritual maturity involves learning to see God's power operating through weakness and His wisdom revealed in apparent foolishness.

Ecclesiological Implications

The theology of the cross has profound implications for understanding the nature and mission of the church. Rather than seeking worldly recognition, political power, or material prosperity, the church is called to embody the cruciform pattern established by Christ.

This means the church's power operates through service, sacrifice, and identification with the suffering rather than through worldly methods of influence or control. The church's greatest victories often appear as defeats to worldly observation, just as Christ's crucifixion appeared to be ultimate defeat while actually achieving ultimate victory.

Theological & Historical Context

Medieval Scholasticism & Natural Theology

The theology of glory finds its most sophisticated expression in medieval scholasticism's attempt to harmonize faith and reason through Aristotelian methodology. Scholars like Thomas Aquinas sought to demonstrate that human reason could arrive at knowledge of God through natural revelation and philosophical demonstration.

While this approach produced sophisticated theological systems, Luther argued that it fundamentally misunderstood the nature of God's revelation. Instead of allowing God to reveal Himself on His own terms through the cross, scholasticism attempted to construct knowledge of God through human categories.

The Reformation Recovery

Luther's articulation of the theology of the cross represented a recovery of biblical theology that had been obscured by centuries of philosophical speculation. The Heidelberg Disputation marked a return to scriptural authority and recognition that God's revelation comes through means that contradict human expectations.

This theological recovery had profound implications for understanding salvation, Christian living, and the nature of the church. It established that theology must be cruciform—shaped by the cross—rather than conforming to human philosophical categories.

Conclusion

The examination of theology of glory versus theology of the cross reveals fundamental differences in approaching God, salvation, and Christian living. The theology of glory, whether in its medieval scholastic form or contemporary prosperity manifestations, seeks to know God through human reason, achieve salvation through human cooperation, and measure blessing through worldly success.

The theology of the cross, firmly grounded in Scripture, recognizes that God reveals Himself supremely through the cross of Christ, that salvation comes entirely by grace through faith, and that spiritual blessing often appears as worldly weakness or failure. 1 Corinthians 1:25 provides the definitive statement: "Because the foolishness of God is wiser than men; and the weakness of God is stronger than men."

This theological framework challenges contemporary Christianity to examine whether its methods, messages, and measures of success align with biblical revelation or human expectation. The cross remains the criterion for authentic Christian theology, calling believers to find God's power in weakness, His wisdom in foolishness, and His glory in humility.

The enduring relevance of this distinction lies in its call to biblical fidelity over cultural accommodation. In an age that values success, prosperity, and positive thinking, the theology of the cross maintains that God's ways are not our ways, and His thoughts are not our thoughts Isaiah 55:8-9. True theological wisdom begins with recognizing that "the cross is laid on every Christian" and that conformity to Christ requires participation in His sufferings as well as His glory.

The theology of the cross thus provides both a hermeneutical key for understanding Scripture and a practical guide for Christian living, ensuring that faith remains anchored in biblical revelation rather than human speculation or cultural expectations. As Paul declared in Galatians 6:14: "But God forbid that I should glory, save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, by whom the world is crucified unto me, and I unto the world."

Also see: