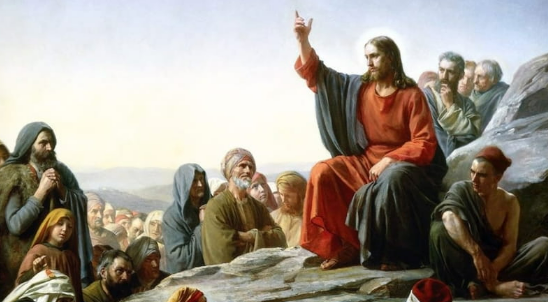

Sermon On The Mount

The Manifesto of The Kingdom: The Sermon On The Mount

Introduction: The Sermon as the Cornerstone of Christian Ethics

The Sermon on the Mount, recorded in chapters five through seven of the Gospel of Matthew, stands as the most comprehensive and foundational body of Jesus's ethical teachings in the New Testament. It is widely regarded as the cornerstone of Christian ethics, a foundational charter that outlines the character, duties, and hopes of the citizens of the Kingdom of Heaven. More than a mere collection of moral aphorisms, the sermon functions as the inaugural manifesto of the Messianic King, a divine constitution for a new covenant community. Its teachings, including the Beatitudes, the Lord's Prayer, and the Golden Rule, have permeated global culture, yet its radical demands continue to challenge and redefine the meaning of discipleship for every generation.

The literary placement of the sermon within Matthew's Gospel is a deliberate act of theological framing. It appears immediately after a summary of Jesus's early Galilean ministry, which is characterized by teaching in synagogues, proclaiming the gospel of the kingdom, and healing every kind of disease. Having demonstrated his power through miraculous works and gathered large crowds, Jesus ascends a mountain to deliver his programmatic address. This positioning establishes the sermon not as an afterthought, but as the foundational definition of the kingdom he has come to inaugurate. It answers two fundamental questions for his followers: what does a citizen of God's kingdom believe, and how, as a result, must they live?.

At its core, the sermon introduces the central theme of a higher righteousness (dikaiosynē), one that must surpass the meticulous, yet often external, piety of the scribes and Pharisees. Jesus systematically reinterprets the Mosaic Law, pushing beyond the letter to expose its deepest intent, which is to transform the inner life, the heart, its motivations, and its allegiances. This internal focus sets the stage for a new ethic grounded not in rule-keeping for its own sake, but in a radical orientation toward God as Father and others as neighbors worthy of love, even enemies.

The sermon's power, however, derives not only from its profound content but also from its narrative presentation as an act of Christological revelation. The entire event is crafted by Matthew to enthrone Jesus as the supreme and authoritative legislator of the Kingdom of God. This is achieved through a convergence of symbolic elements. First, the setting on a mountain is an unmistakable typological parallel to Moses receiving the Law for Israel on Mount Sinai, thereby presenting Jesus as a new and greater Moses, the mediator of a new covenant. Second, Jesus sat down to teach, which was the formal posture of an authoritative rabbi delivering binding instruction, signifying the gravity and official nature of his words. Finally, the sermon concludes with the crowd's reaction: they were astonished at his teaching, for he was teaching them as one who had authority (exousia), and not as their scribes. The scribes cited tradition; Jesus spoke with inherent, divine authority. Thus, the setting, posture, content, and audience reaction all converge to serve a singular narrative purpose: to portray Jesus not merely as a teacher, but as the enthroned Messianic King, proclaiming the law of his kingdom.

Part I: Context & Composition

1.1 The Mountain and the Multitudes: Historical and Literary Setting

The historical and geographical backdrop of the Sermon on the Mount, while not specified with absolute certainty in the text, is deeply rooted in the landscape of Jesus's Galilean ministry. Christian tradition, dating back to the early centuries, identifies the location as the Mount of Beatitudes, a hill known in antiquity as Mt. Eremos, situated on the northwestern shore of the Sea of Galilee between the ancient towns of Capernaum and Tabgha. This location offers a commanding view of the sea and the fertile Plain of Gennesaret, a region central to Jesus's work of preaching and healing. The topography of the Galilean hillsides, characterized by elevated terrain with numerous flat, level areas, provides a plausible setting for the events described. Such locations often create natural amphitheaters, where acoustics are amplified, making them ideal for a speaker to address the large crowds that followed Jesus.

While the scriptural account does not name the specific mountain, the antiquity of the tradition lends it significant weight. This is supported by archaeological evidence, most notably the remains of a Byzantine-era church dating to the late 4th century, discovered at the foot of the hill. The existence of this structure, built to commemorate the sermon shortly after Christianity was legalized in the Roman Empire, indicates that early Christians venerated this specific site as a holy place connected to Jesus's teaching ministry. The modern Church of the Beatitudes, an octagonal chapel built in 1938, now stands at the summit, continuing this long tradition of veneration.

Within the literary architecture of the Gospel of Matthew, the sermon's placement is profoundly significant. It serves as the first of five major discourses delivered by Jesus, a structural choice that many scholars believe intentionally mirrors the five books of the Torah (the Pentateuch). This five-fold structure reinforces Matthew's primary theological objective: to present Jesus as the promised Messiah and a "New Moses," who has come not to abolish the Law but to bring it to its ultimate fulfillment. The sermon is strategically positioned after the narrative of Jesus's baptism, his temptation in the wilderness, and the calling of his first disciples. It thus functions as the foundational charter for this nascent community of followers, articulating the ethical and spiritual principles that will define their lives.

The audience for this foundational teaching is described with a subtle but important distinction. The narrative begins with Jesus seeing the crowds and consequently going up the mountain. Once there, his disciples came to him, and the text states that he opened his mouth and taught them. This suggests that the primary recipients of this intensive instruction are the committed inner circle of disciples. However, the crowds remain present, as they are explicitly mentioned again in the conclusion, where their astonishment is recorded in Matthew 7:28. This dual audience implies that the sermon has a dual function: it is both a detailed manual of discipleship for the committed and a public proclamation of the kingdom's standards to all who would listen.

1.2 A Tale of Two Sermons: A Comparative Analysis with Luke's Sermon on the Plain

A comprehensive study of the Sermon on the Mount necessitates a comparative analysis with its parallel account in the Gospel of Luke 6:17-49. This shorter version, commonly known as the Sermon on the Plain, shares significant thematic and verbal overlap with Matthew's account but also exhibits striking differences in setting, structure, content, and theological emphasis. The relationship between these two sermons has been a subject of extensive scholarly debate, with theories ranging from their being reports of two distinct preaching events to their being different authorial redactions of the same body of traditional sayings of Jesus.

A surface-level reading might present the differences as a historical contradiction: Did Jesus deliver this teaching on a mountain or on a plain? Were the blessings directed at the "poor in spirit" or the socio-economically "poor"? While some have sought to harmonize these discrepancies, suggesting, for instance, that Jesus preached from a level place on the side of a mountain, a more profound understanding emerges when the differences are viewed not as historical problems to be solved but as deliberate theological artistry. The evangelists were not mere stenographers; they were theologians who shaped their material to communicate a particular portrait of Jesus to a particular audience. Matthew's portrayal of Jesus as the New Moses, the authoritative interpreter and fulfillment of the Torah, is perfectly served by the majestic and law-giving symbolism of a "Sermon on the Mount". Conversely, Luke's consistent emphasis on Jesus's mission to the poor, the marginalized, and the Gentiles is powerfully underscored by a "Sermon on the Plain," with its accessible setting, inclusive audience, and focus on socio-economic justice. The variations, therefore, are not a flaw in the record but a feature of inspired literary and theological craftsmanship, offering two complementary perspectives on the same foundational teachings.

The key distinctions between the two accounts can be systematically organized for clarity.

| Aspect | Sermon on the Mount in Matthew 5-7 | Sermon on the Plain in Luke 6:17-49 |

|---|---|---|

| Setting | On a mountain in Matthew 5:1 | On a "in the plain" in Luke 6:17 |

| Symbolism | Authority, connection to Moses and Sinai | Accessibility, inclusivity, among the people |

| Length | Longer (107 verses) | Shorter (30 verses) |

| Audience | Primarily disciples, with crowds listening; Jewish-Christian focus | Disciples and a broad multitude, including Gentiles; universal focus |

| Beatitudes | 8 spiritual beatitudes (such as "poor in spirit") | 4 blessings and 4 woes with a socio-economic focus (such as "be ye poor") |

| Key Theme | Inward transformation and a "higher righteousness" that fulfills the Law | Social justice, reversal of fortunes, and God's care for the marginalized |

| Relation to Law | Explicit focus: "Think not that I am come to destroy the law....but to fulfil" in Matthew 5:17 | Implicit; teachings stand on their own authority without direct reference to fulfilling the Law |

The most pronounced difference lies in the Beatitudes. Matthew's eight blessings focus on internal, spiritual dispositions: being "poor in spirit," mourning over sin, hungering for righteousness. They describe the character of a disciple regardless of external circumstances. Luke, in contrast, presents four blessings that are starkly physical and economic—"Blessed be ye poor... Blessed are ye that hunger now... Blessed are ye that weep now"—and pairs them with four corresponding "woes" directed at the rich, the well-fed, and the laughing. Luke's version is a radical proclamation of social reversal, a theme central to his Gospel, where God's kingdom turns the world's values upside down. Together, the two accounts provide a stereoscopic vision of the kingdom: it demands both inner spiritual transformation and a radical commitment to justice for the poor and oppressed.

Part II: An Exegetical Journey Through The Sermon

2.1 The Charter of the Kingdom: The Beatitudes in Matthew 5:3-12

3. Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

4. Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted.

5. Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth.

6. Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled.

7. Blessed are the merciful: for they shall obtain mercy.

8. Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God.

9. Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God.

10. Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

11. Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake.

12. Rejoice, and be exceeding glad: for great is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you.

The Sermon on the Mount opens not with a list of commands, but with the Beatitudes, a series of nine declarative blessings that function as the foundational charter of the kingdom. These statements are not prerequisites for entry but are descriptions of the character and eschatological promise for those who are already citizens of this new reality. The Greek term makarios, translated as "blessed," conveys a sense of divine favor and profound, God-given happiness or fortune, a state of well-being independent of worldly circumstances. Each beatitude presents a paradox: it pronounces as "blessed" those whom the world would consider unfortunate or weak, thereby subverting conventional wisdom and revealing the value system of God's kingdom.

The first beatitude, "Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven" in Matthew 5:3, sets the tone for all that follows. To be "poor in spirit" is not necessarily to be materially poor, but to recognize one's profound spiritual bankruptcy and complete dependence on God. It is the humility that acknowledges one has nothing to offer God and can only receive the kingdom as a gift of sheer grace. This posture of radical dependence is the very doorway into the kingdom.

"Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted" in Matthew 5:4. This mourning is not mere sadness over personal loss, but a deep grief over the reality of sin, both one's own and the brokenness it has caused in the world. It is the sorrow of those who see the world as it is in light of God's holiness. To them is promised the ultimate divine comfort, an eschatological solace that will wipe away every tear.

"Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth" in Matthew 5:5. Meekness, in the biblical sense, is not weakness or a timid disposition. It is strength under control, a gentleness of spirit that is born of submission to God's will. The meek person forgoes self-assertion and retaliation, trusting in God for vindication. The promise that they will "inherit the earth" is a direct allusion to Psalm 37:11 and points to a future, restored creation where God's gentle rule prevails.

"Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled." (5:6). This describes an intense, all-consuming desire for both personal holiness and the establishment of God's justice in the world. It is a craving that can only be filled by God himself, who promises complete satisfaction in the consummated kingdom.

The subsequent beatitudes describe the active virtues that flow from this foundational character.

"Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy" in Matthew 5:7 establishes a principle of divine reciprocity: those who extend compassion and forgiveness to others will themselves be recipients of God's mercy.

"Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God" in Matthew 5:8 moves to the core of internal integrity. Purity of heart signifies an undivided devotion to God, a sincerity of motive that is free from duplicity. This inner clarity is the prerequisite for the ultimate beatific vision: seeing God.

"Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God" in Matthew 5:9 highlights the vocation of kingdom citizens to be agents of reconciliation, reflecting the character of their Father, the "God of peace".

The final beatitudes pivot to the inevitable consequence of living out this counter-cultural ethic: "Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness' sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven" in Matthew 5:10-12. Jesus makes it clear that a life aligned with the kingdom will provoke hostility from the world. He links this suffering directly to the legacy of the Old Testament prophets, who were also persecuted for speaking God's truth. This persecution is not a sign of failure but a badge of honor, a confirmation of one's allegiance to Christ, for which the reward in heaven is great.

2.2 The Vocation of Discipleship: Salt and Light in Matthew 5:13-16

13. Ye are the salt of the earth: but if the salt have lost his savour, wherewith shall it be salted? it is thenceforth good for nothing, but to be cast out, and to be trodden under foot of men.

14. Ye are the light of the world. A city that is set on an hill cannot be hid.

15. Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that are in the house.

16. Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in heaven.

Immediately following the Beatitudes, Jesus employs two powerful metaphors to define the identity and function of his disciples in the world: they are "the salt of the earth" and "the light of the world". These are not commands to become something they are not, but declarations of what they are by virtue of their connection to him and their embodiment of the kingdom character just described. The vocation of discipleship is one of transformative influence.

The metaphor of "salt of the earth" in Matthew 5:13 would have resonated deeply in the ancient world, where salt had multiple crucial functions. Primarily, it was a preservative, used to prevent decay and corruption in food. In the same way, disciples are to act as a moral and spiritual preservative in society, arresting its decay and pointing to a better way. Salt also served as a flavor-enhancing agent, bringing out the best in food. Disciples are likewise called to bring a flavor of goodness, joy, and divine life to a bland world. Jesus's stark warning: "but if the salt have lost his savour, wherewith shall it be salted? it is thenceforth good for nothing, but to be cast out, and to be trodden under foot of men" is a call for his followers to maintain their distinctiveness. A disciple who has assimilated to the world's values has lost their purpose and influence.

The second metaphor, "light of the world" in Matthew 5:14-16, builds on a significant Old Testament theme, where Israel was called to be a light to the Gentiles in Isaiah 42:6, Isaiah 49:6. Jesus now transfers this identity to his community of followers. Light, by its nature, is meant to be seen; it dispels darkness and reveals the way. Jesus uses the image of a town built on a hill that cannot be hidden and a lamp placed on a stand, not under a bowl, to emphasize that the disciples' faith and life are not to be private matters. Their "good deeds" are the visible evidence of their transformed character. Crucially, the purpose of this visibility is not self-glorification. Jesus commands, "Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in heaven". This sets a key principle for the entire sermon: the ultimate aim of Christian ethics is doxological, it is to point people away from the disciple and toward God the Father. This theme will be revisited and amplified in the teachings on piety in Matthew Chapter 6.

2.3 The Higher Righteousness: Jesus and the Fulfillment of the Torah in Matthew 5:17-48

This section constitutes the theological heart of the Sermon on the Mount, where Jesus defines his relationship to the sacred traditions of Israel and articulates the "higher righteousness" required of kingdom citizens. He begins with a programmatic statement of immense importance: "Think not that I am come to destroy the law, or the prophets: I am not come to destroy, but to fulfil" in Matthew 5:17. This declaration counters any suspicion that his teaching represents a new, antinomian religion. Instead, Jesus positions himself in deep continuity with the Hebrew Scriptures. The term "fulfill" (plērōsai) is multifaceted; it means to bring the Torah to its intended goal, to reveal its deepest meaning, and to embody its principles perfectly in his own life and teaching. He affirms the eternal validity of the Law, down to its "one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass" in Matthew 5:18.

Having established his fidelity to the Torah, Jesus proceeds to demonstrate its true intent through a series of six illustrations, commonly known as the "antitheses". Each follows the pattern: "Ye have heard that it was said by them of old time, Thou shalt not kill; and whosoever shall kill shall be in danger of the judgment: But I say unto you, That whosoever is angry with his brother without a cause shall be in danger of the judgment: and whosoever shall say to his brother, Raca, shall be in danger of the council: but whosoever shall say, Thou fool, shall be in danger of hell fire". In these statements, Jesus is not contradicting or annulling the Mosaic Law. Rather, he is contrasting the traditional, often superficial, interpretation of the scribes with his own authoritative, radical interpretation that penetrates to the level of the heart, exposing the internal roots of external sin.

-

On Anger in Matthew 5:21-26: The Law said, "Thou shalt not kill" Jesus radicalizes this by tracing the act of murder to its source: unrighteous anger, contemptuous speech ("Raca"), and condemnation of a brother ("Thou fool!"). In the kingdom's economy, the internal attitude is as culpable before God as the external act. He underscores the urgency of reconciliation, stating that it takes precedence even over religious worship.

-

On Lust in Matthew 5:27-30: The Law said, "Thou shalt not commit adultery" Jesus internalizes this command, identifying the lustful look as adultery committed in the heart. He uses shocking hyperbole, gouging out an eye or cutting off a hand to illustrate the extreme measures one must take to deal radically with the root causes of sin.

-

On Divorce in Matthew 5:31-32: The traditional interpretation allowed for divorce with a certificate. Jesus severely restricts this provision, permitting it only on the grounds of "fornication" (

porneia), thereby upholding the sanctity and permanence of the marriage covenant as God intended it from the beginning. -

On Oaths in Matthew 5:33-37: The Law regulated oaths, prohibiting false vows. Jesus goes further, forbidding oaths altogether in everyday speech. The need for oaths, he implies, arises from a culture of deceit. In the kingdom, a disciple's integrity should be so absolute that their simple "yea" or "nay" is sufficient.

-

On Retaliation in Matthew 5:38-42: The Law prescribed the lex talionis ("an eye for an eye"), a principle of proportional justice intended to limit vengeance in a legal context. Jesus abrogates this as a principle for personal ethics, commanding his followers to practice non-retaliation and extravagant generosity: to turn the other cheek, give up one's cloak, go the second mile, and give to those who ask. This is a call to break the cycle of violence with proactive love.

-

On Love for Enemies in Matthew 5:43-48: This is the climax and the most radical of the antitheses. The traditional teaching was to "love thy neighbor," which was often interpreted as implying permission to "hate thine enemy." Jesus shatters this boundary, commanding his followers to love their enemies and pray for their persecutors. The theological rationale for this is profound: disciples are to imitate the character of their heavenly Father, who demonstrates impartial love by giving the blessings of sun and rain to both the righteous and the unrighteous.

This entire section culminates in the impossibly high demand of Matthew 5:48: "Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect". This is not a call to sinless perfectionism in this life, but an exhortation to a wholeness and integrity of character that reflects the very nature of God himself, particularly his all-embracing love. It is the ultimate summary of the "higher righteousness" that the sermon proclaims.

2.4 The Piety of the Heart: On Almsgiving, Prayer, and Fasting in Matthew 6:1-18

- Take heed that ye do not your alms before men, to be seen of them: otherwise ye have no reward of your Father which is in heaven.

- Therefore when thou doest thine alms, do not sound a trumpet before thee, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and in the streets, that they may have glory of men. Verily I say unto you, They have their reward.

- But when thou doest alms, let not thy left hand know what thy right hand doeth:

- That thine alms may be in secret: and thy Father which seeth in secret himself shall reward thee openly.

- And when thou prayest, thou shalt not be as the hypocrites are: for they love to pray standing in the synagogues and in the corners of the streets, that they may be seen of men. Verily I say unto you, They have their reward.

- But thou, when thou prayest, enter into thy closet, and when thou hast shut thy door, pray to thy Father which is in secret; and thy Father which seeth in secret shall reward thee openly.

- But when ye pray, use not vain repetitions, as the heathen do: for they think that they shall be heard for their much speaking.

- Be not ye therefore like unto them: for your Father knoweth what things ye have need of, before ye ask him.

- After this manner therefore pray ye: Our Father which art in heaven, Hallowed be thy name.

- Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven.

- Give us this day our daily bread.

- And forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors.

- And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil: For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, for ever. Amen.

- For if ye forgive men their trespasses, your heavenly Father will also forgive you:

- But if ye forgive not men their trespasses, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses.

- Moreover when ye fast, be not, as the hypocrites, of a sad countenance: for they disfigure their faces, that they may appear unto men to fast. Verily I say unto you, They have their reward.

- But thou, when thou fastest, anoint thine head, and wash thy face;

- That thou appear not unto men to fast, but unto thy Father which is in secret: and thy Father, which seeth in secret, shall reward thee openly.

After establishing the radical internal demands of the kingdom's righteousness, Jesus turns to the external practices of religious life. He addresses the three central pillars of first-century Jewish piety: almsgiving (charity), prayer, and fasting. The unifying theme throughout this section is a sharp critique of performative religion, righteous acts done for the purpose of gaining public acclaim. Jesus labels those who practice such piety "hypocrites," a Greek term for stage actors, implying that their devotion is a mere performance for a human audience. Their reward, he states, is the fleeting praise of others; they have already received it in full and should expect nothing from God.

In contrast, Jesus commends a piety of the heart, one whose sole audience is the heavenly Father "seeth in secret himself". For each of the three practices, he presents a clear pattern: a warning against hypocritical, public display, followed by an instruction for secret, sincere devotion, and concluding with a promise of reward from the Father. When giving to the needy, disciples should not "sound a trumpet" but give so secretly that it is as if their "left hand" does not know what their "right hand is doing", a hyperbolic expression for un-self-conscious, uncalculated generosity. When praying, they are to avoid the ostentatious public displays of the hypocrites and instead enter a private room, shut the door, and pray to the Father in secret. When fasting, they are to avoid looking miserable and disheveled to advertise their piety, but should groom themselves as normal so that only the Father is aware of their devotion. The principle is clear: the motivation behind religious practice is what determines its value before God.

At the heart of this section on piety, Jesus provides his disciples with a model for prayer, now famously known as The Lord's Prayer in Matthew 6:9-13. He prefaces it by warning against the Gentile practice of using "vain repetitions," as if prayer's effectiveness depends on the quantity of words. Instead, he offers a prayer that is remarkable for its brevity, simplicity, and theological depth. It is not a rigid formula to be recited mindlessly, but a pattern (houtōs, "after this manner") that teaches the priorities and posture of kingdom prayer.

The prayer's structure itself is a lesson in theology. It begins not with human needs but with God's glory, containing two sets of petitions. The first three are "thy" petitions, focusing on God's priorities:

-

"Hallowed be thy name": A plea that God's name would be regarded as holy and honored throughout the world.

-

"Thy kingdom come": The central petition, asking for the full realization of God's sovereign rule.

-

"Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven": A prayer for the alignment of human life with the divine will.

Only after orienting the heart toward God does the prayer turn to human needs in the three "us" petitions:

-

"Give us this day our daily bread": A simple petition for daily provision, expressing trust and dependence on the Father.

-

"And forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors": A plea for forgiveness that is inextricably linked to the disciple's willingness to forgive others. Jesus underscores this point immediately after the prayer in Matthew 6:14-15.

-

"And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil": A request for divine guidance and protection in the face of spiritual trials and the power of the evil one.

This model prayer functions as a microcosm of the entire Sermon on the Mount. It encapsulates the sermon's central themes in devotional form. The petition "Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven" is the very essence of the sermon's proclamation. The desire for righteousness is reflected in "hallowed be thy name." The emphasis on mercy and forgiveness resonates with Jesus's teachings in Matthew Chapters 5 and Matthew Chapter 7. The trust in the Father for provision anticipates the instruction against anxiety that follows, and the plea for deliverance acknowledges the spiritual struggle inherent in choosing the "narrow way". Thus, the Lord's Prayer is not merely one topic among many; it is the devotional heart of the sermon, providing a template for the disciple to internalize and pray back to God the very kingdom realities the sermon proclaims.

2.5 The Singular Focus: Treasures, Anxiety, and Trust in Matthew 6:19-34

19. Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth, where moth and rust doth corrupt, and where thieves break through and steal:

20. But lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust doth corrupt, and where thieves do not break through nor steal:

21. For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also.

22. The light of the body is the eye: if therefore thine eye be single, thy whole body shall be full of light.

23. But if thine eye be evil, thy whole body shall be full of darkness. If therefore the light that is in thee be darkness, how great is that darkness!

24. No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate the one, and love the other; or else he will hold to the one, and despise the other. Ye cannot serve God and mammon.

25. Therefore I say unto you, Take no thought for your life, what ye shall eat, or what ye shall drink; nor yet for your body, what ye shall put on. Is not the life more than meat, and the body than raiment?

26. Behold the fowls of the air: for they sow not, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feedeth them. Are ye not much better than they?

27. Which of you by taking thought can add one cubit unto his stature?

28. And why take ye thought for raiment? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin:

29. And yet I say unto you, That even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these.

30. Wherefore, if God so clothe the grass of the field, which to day is, and to morrow is cast into the oven, shall he not much more clothe you, O ye of little faith?

31. Therefore take no thought, saying, What shall we eat? or, What shall we drink? or, Wherewithal shall we be clothed?

32. (For after all these things do the Gentiles seek:) for your heavenly Father knoweth that ye have need of all these things.

33. But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you.

34. Take therefore no thought for the morrow: for the morrow shall take thought for the things of itself. Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof.

This section of the sermon addresses the deeply spiritual issues of materialism and anxiety, exposing them as symptoms of a divided heart and a failure to trust in God's fatherly care. Jesus presents a series of teachings that call for a radical reorientation of one's ultimate allegiance and source of security.

The discourse begins with a command regarding treasures: "Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth, where moth and rust doth corrupt, and where thieves break through and steal: But lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust doth corrupt, and where thieves do not break through nor steal" in Matthew 6:19-20. Jesus contrasts the ephemeral and vulnerable nature of earthly wealth, subject to moths, rust, and thieves with the eternal security of heavenly treasure. This is not merely financial advice; it is a matter of ultimate value. He provides the diagnostic principle: "For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also" in Matthew 6:21. A person's investments reveal their deepest love and loyalty.

This leads to the stark declaration that a divided loyalty is impossible: "No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate the one, and love the other; or else he will hold to the one, and despise the other. Ye cannot serve God and mammon" in Matthew 6:24. "Mammon" is the Aramaic word for wealth, personified here as a rival deity demanding allegiance. Jesus forces a choice, asserting that one will inevitably love one and hate the other. There is no neutrality; the human heart must have a single, ultimate master.

The prohibition against anxiety flows directly from this principle of singular trust in God. The repeated command, "take no thought" in Matthew 6:25, Matthew 6:31, Matthew 6:34, is not a call for irresponsible improvidence but a call to reject the paralyzing fear that comes from trusting in oneself or in material possessions. Jesus grounds this command in a profound theological argument about the nature of God as a provident Father. He points to the natural world as evidence of God's care: if the Father feeds the birds of the air and clothes the lilies of the field with a glory surpassing Solomon's, how much more will he care for his own children? Worry is portrayed as both futile ("Which of you by taking thought can add one cubit unto his stature?") and characteristic of pagan unbelief ("For after all these things do the Gentiles seek").

The antidote to anxiety is not simply to stop worrying, but to actively reorder one's priorities. Jesus provides the summary command for this entire section: "But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you" in Matthew 6:33. When a disciple's primary pursuit is the advancement of God's rule and the cultivation of a righteous life, the secondary concerns of material provision are placed in their proper perspective, entrusted to the care of a Father who already knows all their needs.

2.6 The Community Ethic: On Judging and the Golden Rule in Matthew 7:1-12

- Judge not, that ye be not judged.

- For with what judgment ye judge, ye shall be judged: and with what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again.

- And why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother’s eye, but considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye?

- Or how wilt thou say to thy brother, Let me pull out the mote out of thine eye; and, behold, a beam is in thine own eye?

- Thou hypocrite, first cast out the beam out of thine own eye; and then shalt thou see clearly to cast out the mote out of thy brother’s eye.

- Give not that which is holy unto the dogs, neither cast ye your pearls before swine, lest they trample them under their feet, and turn again and rend you.

- Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you:

- For every one that asketh receiveth; and he that seeketh findeth; and to him that knocketh it shall be opened.

- Or what man is there of you, whom if his son ask bread, will he give him a stone?

- Or if he ask a fish, will he give him a serpent?

- If ye then, being evil, know how to give good gifts unto your children, how much more shall your Father which is in heaven give good things to them that ask him?

- Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them: for this is the law and the prophets.

In the final chapter of the sermon's main body, Jesus shifts his focus to the ethical principles that must govern relationships within the community of disciples. This section begins with one of the most famous and frequently misinterpreted of his teachings: "Judge not, that ye be not judged." in Matthew 7:1.

This command is not a prohibition against all forms of moral discernment or critical evaluation. The context of the sermon itself, with its sharp distinctions between righteousness and unrighteousness and its later warning against false prophets in Matthew 7:15-20, makes such an interpretation impossible. Rather, Jesus is condemning a specific kind of judgment: that which is hypocritical, censorious, and condemnatory. He warns that the standard of judgment we apply to others will be the very standard applied to us by God: "For with what judgment ye judge, ye shall be judged: and with what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again." in Matthew 7:2.

To illustrate the absurdity of hypocritical judgment, Jesus uses the memorable and humorous image of a person with a log (dokos) in their own eye attempting to remove a tiny speck (karphos) from their brother's eye. The command is not to ignore the speck in the brother's eye, but to deal with one's own, far greater, fault first. "Thou hypocrite, first cast out the beam out of thine own eye; and then shalt thou see clearly to cast out the mote out of thy brother's eye" in Matthew 7:5. This demands a posture of profound humility and rigorous self-examination as the necessary prerequisite for any attempt at constructive fraternal correction.

Following a brief and somewhat enigmatic saying about not giving "Give not that which is holy unto the dogs, neither cast ye your pearls before swine," in Matthew 7:6, likely a warning about exercising discernment and not persisting in offering the precious truth of the gospel to those who violently and persistently reject it, Jesus transitions to a teaching on prayer and the goodness of God. The threefold exhortation to "Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you" in Matthew 7:7 is accompanied by a threefold promise of receiving, finding, and having the door opened. This is an encouragement to persistent, confident prayer, grounded in the character of God as a benevolent Father who gives good gifts to his children, far exceeding the generosity of even evil human fathers.

This reflection on God's generous nature provides the immediate context for the ethical climax of this section: The Golden Rule. In Matthew 7:12, Jesus declares: "Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them: for this is the law and the prophets". This statement is monumental. It functions as a comprehensive summary of the entire ethical demand of the Hebrew Scriptures. What sets Jesus's formulation apart from similar maxims in other ancient philosophies is its positive and proactive nature. Many other traditions phrased the rule negatively ("Do not do to others what you would not have them do to you"), which requires only restraint. Jesus's positive command requires active empathy and initiative. It compels the disciple to imagine what they would desire in another's situation—kindness, mercy, help, respect—and then to take the first step in providing it. It is the practical application of the command to love one's neighbor as oneself.

2.7 The Call to Decision: Two Ways, Two Trees, Two Foundations in Matthew 7:13-29

13. Enter ye in at the strait gate: for wide is the gate, and broad is the way, that leadeth to destruction, and many there be which go in thereat:

14. Because strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it.

15. Beware of false prophets, which come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravening wolves.

16. Ye shall know them by their fruits. Do men gather grapes of thorns, or figs of thistles?

17. Even so every good tree bringeth forth good fruit; but a corrupt tree bringeth forth evil fruit.

18. A good tree cannot bring forth evil fruit, neither can a corrupt tree bring forth good fruit.

19. Every tree that bringeth not forth good fruit is hewn down, and cast into the fire.

20. Wherefore by their fruits ye shall know them.

21. Not every one that saith unto me, Lord, Lord, shall enter into the kingdom of heaven; but he that doeth the will of my Father which is in heaven.

22. Many will say to me in that day, Lord, Lord, have we not prophesied in thy name? and in thy name have cast out devils? and in thy name done many wonderful works?

23. And then will I profess unto them, I never knew you: depart from me, ye that work iniquity.

24. Therefore whosoever heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them, I will liken him unto a wise man, which built his house upon a rock:

25. And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell not: for it was founded upon a rock.

26. And every one that heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them not, shall be likened unto a foolish man, which built his house upon the sand:

27. And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell: and great was the fall of it.

28. And it came to pass, when Jesus had ended these sayings, the people were astonished at his doctrine:

29. For he taught them as one having authority, and not as the scribes.

The sermon's conclusion is not a gentle summary but a series of urgent and stark warnings that force a decision upon every person in the audience. Jesus presents a sequence of three binary oppositions, leaving no middle ground. The path of discipleship requires a definitive choice.

First is the image of the two gates and two ways in Matthew 7:13-14. The gate to destruction is wide and the road is broad and easy, traveled by the many. In contrast, the gate to life is narrow and the way is hard, and only a few find it. This metaphor powerfully illustrates that the life of the kingdom, as outlined in the sermon, is a difficult and demanding path. It runs counter to the easy, conventional ways of the world and requires deliberate effort and commitment to enter and remain on it.

Second is the test of the two trees in Matthew 7:15-20. This teaching is presented in the context of a warning against "false prophets" who appear outwardly harmless ("in sheep's clothing") but are inwardly ravenous wolves. The test for discerning their true nature is their fruit: "Even so every good tree bringeth forth good fruit; but a corrupt tree bringeth forth evil fruit". This principle applies not only to teachers but to all who claim to be disciples. The "fruit" is the tangible evidence of one's character and actions. A life that consistently produces unrighteousness, regardless of its religious claims, reveals a corrupt heart, which is destined for judgment ("is hewn down, and cast into the fire").

Third, and most sobering, is the parable of the two foundations in Matthew 7:24-27, which is framed by a warning against false profession. Jesus declares that not everyone who makes a verbal claim of allegiance "Lord, Lord, shall enter into the kingdom of heaven; but he that doeth the will of my Father which is in heaven". He foretells a day of judgment where many who performed impressive religious acts (prophesying, casting out demons, doing miracles) in his name will be rejected with the terrifying words, ", I never knew you: depart from me, ye that work iniquity". True discipleship is not defined by charismatic gifts or verbal profession, but by obedience.

This leads directly to the final parable. The wise builder is the one who hears Jesus's words, the very words of this sermon and puts them into practice. This person builds their life on the unshakeable foundation of the rock. The foolish builder is the one who hears the same words but fails to obey. This person builds on the shifting foundation of sand. The coming storm which is a metaphor for the trials of life and the final judgment will inevitably come, revealing the true nature of each person's foundation. The house built on the rock of obedience will stand; the house built on the sand of mere hearing will collapse in a great ruin. The sermon thus ends with an unequivocal call to action. Hearing is not enough; only a life of active obedience to the teachings of the King constitutes a wise and saving response.

Part III: The Theological Landscape of The Sermon

3.1 The Constitution of the Kingdom: Law, Grace, and Christian Ethics

A central and enduring question in the interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount is its relationship to the concepts of law and grace. Does its series of demanding, seemingly impossible commands constitute a new, more rigorous law, leading to a system of works-righteousness? Or is it, in fact, an expression of the gospel of grace? A purely legalistic reading fails to grasp the sermon's deeper theological function within Matthew's narrative and Christian doctrine.

The impossibly high standard set by Jesus by culminating in the command, "Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect" in Matthew 5:48 serves a crucial purpose akin to that of the Mosaic Law in Pauline theology: it exposes the profound depth of human sinfulness and our utter inability to achieve the righteousness God requires on our own strength. By internalizing the law's demands, moving from the act of murder to the attitude of anger, from adultery to the lustful glance, Jesus leaves no room for self-righteousness. He demonstrates that on the level of the heart, all have fallen short of God's perfect standard. In this sense, the sermon functions to "kill" before it can "make alive". It dismantles any hope of self-salvation and drives the listener to recognize their desperate need for a righteousness that must come from outside themselves.

This is where the sermon intersects with the gospel of grace. It is not a ladder of moral achievement to climb into the kingdom, but rather a description of the character and conduct of those who have already entered it by grace. The sermon describes the fruit of a transformed life, not the requirements to earn that transformation. The righteousness that exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees is not a higher degree of human effort, but a different kind of righteousness altogether, one that is received as a gift through faith in Christ. Jesus is not only the teacher of the sermon but also its sole perfect practitioner. He is the one who has fulfilled the law on behalf of his people. Therefore, the sermon ultimately leads the thoughtful reader to the foot of the cross, the place where the grace that makes such a life possible is secured. The Christian life, then, is an endeavor to live out the sermon's ethic, not to earn salvation, but in grateful response to the salvation already received, empowered by the Holy Spirit.

3.2 Inaugurated Eschatology: Living in the "Already and Not Yet"

The ethical framework of the Sermon on the Mount is incomprehensible apart from its eschatological orientation. Its teachings are best understood through the theological lens of "inaugurated eschatology," which recognizes that with the coming of Jesus, the Kingdom of God has broken into human history ("already") but has not yet arrived in its final, consummated form ("not yet").

The sermon is, in essence, the ethic of the age to come, proclaimed as the standard for life in the present age. The blessings of the kingdom are both present realities and future hopes. The Beatitudes exemplify this tension: the poor in spirit are blessed because "theirs is the kingdom of heaven" (a present possession), while those who mourn are blessed because "they shall be comforted" (a future promise). Disciples are called to store up treasures in heaven for a future reward in Matthew 6:20 and to pray for the future coming of the kingdom in Matthew 6:10, while simultaneously living as citizens of that kingdom in the here and now.

This "already and not yet" framework explains the radical and seemingly impractical nature of the sermon's commands. The injunctions to love enemies, turn the other cheek, and forgo anxiety about material needs are the norms of the perfected kingdom of God, where God's rule is absolute and his provision is complete. By calling his followers to live by these ethics in a world still marked by violence, enmity, and scarcity, Jesus is calling them to be a living signpost, a colony of heaven on earth, bearing witness to the reality of the future kingdom that has already begun to dawn in him. Their successes in living out this ethic are evidence that the kingdom is already present; their failures serve as a poignant reminder that it is not yet fully here and that their own lives, and the world itself, are still in need of final redemption. The Christian, therefore, lives in the tension of striving to embody the life of the future in the midst of the present.

3.3 The Christological Proclamation: Jesus as New Moses, Divine Sage, and King

While the Sermon on the Mount is primarily a discourse on ethics and discipleship, it is simultaneously a profound proclamation about the identity of the one who delivers it. Jesus's person is inseparable from his teaching; what he says reveals who he is. The sermon presents a multifaceted Christology, portraying Jesus in at least three supreme roles.

First, as previously established, Jesus is presented as the New Moses. The setting on the mountain, the gathering of God's people, and the delivery of a foundational law all evoke the imagery of Sinai. However, Jesus is not merely a second Moses; he is a greater one. Whereas Moses relayed the law he received from God, Jesus speaks with an unmediated authority, repeatedly contrasting the old revelation with his own definitive word: "Ye have heard that it was said by them of old time, Thou shalt not kill; and whosoever shall kill shall be in danger of the judgment: But I say unto you". He is not just a channel of the law; he is its fulfillment and its source.

Second, Jesus is portrayed as the Divine Sage. The sermon's literary form with its use of beatitudes (makarisms), proverbial wisdom, and ethical instruction aligns with the tradition of ancient wisdom literature. Jesus is presented as the ultimate teacher of wisdom, the one who reveals the true path to human flourishing and a life lived in harmony with the created order. Yet, his wisdom is not merely human insight; it is divine revelation about the nature of God and his kingdom. He embodies the divine wisdom he proclaims.

Third, and most significantly, Jesus is revealed as the Messianic King and Judge. He is the one who inaugurates the Kingdom of Heaven and legislates its constitution. He speaks with the authority of a sovereign, not as a scribe interpreting past texts. His teaching is the standard by which all humanity will ultimately be judged. This is made explicit in the sermon's conclusion, where Jesus casts himself in the role of the eschatological judge. It is to him that people will say, "Lord, Lord," on the final day, and it is he who will pronounce the verdict: "I never knew you; depart from me". He is the king who embodies the law he proclaims and the judge who will enforce its terms. The sermon is not just the teaching of the King; it is a teaching that reveals the King himself.

Part IV: A History of Reception & Interpretation

The Sermon on the Mount has been a source of inspiration, debate, and controversy throughout the history of the church. Its radical demands have consistently challenged believers to grapple with its applicability to their lives. The history of its interpretation is not merely a record of evolving exegetical ideas; it serves as a sensitive barometer, reflecting the church's changing self-perception (ecclesiology) and its ever-shifting relationship with the surrounding culture and state power. When the church has existed as a distinct, counter-cultural minority, it has often gravitated toward a literal, absolutist reading of the sermon as a defining charter. Conversely, when the church has been integrated with the structures of worldly power, interpretive strategies have emerged to mediate the tension between the sermon's radical ethic and the pragmatic demands of governing a society.

4.1 The Patristic Period: Augustine and the "Perfect Standard"

In the early centuries, the church fathers generally approached the Sermon on the Mount as a straightforward ethical guide, providing the normative expectations for the life of every Christian. It was a practical document for discipleship. Apologetically, it was used to defend the faith against figures like Marcion, who rejected the Old Testament; the sermon's theme of fulfillment in Matthew 5:17 demonstrated Christianity's rootedness in the Hebrew Scriptures. Polemically, it was used to argue for the superiority of Christian morality over both Judaism and paganism. Despite acknowledging the difficulty of its demands, early writers like Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Origen viewed obedience to the sermon as the expected response of a believer.

The most influential patristic interpretation came from Augustine of Hippo (354-430 AD). In his seminal work, Our Lord's Sermon on the Mount, Augustine declared it to be "the perfect standard of the Christian Life". His approach was deeply pastoral and spiritual. He famously structured his analysis around a model of spiritual ascent, meticulously mapping the first seven Beatitudes onto the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit enumerated in Isaiah 11:2-3.59 For Augustine, the spiritual journey begins with the "fear of the Lord" (corresponding to poverty of spirit) and ascends through piety, knowledge, fortitude, counsel, and understanding, culminating in wisdom (corresponding to the peacemakers). This framework, which integrated the sermon's ethics into a comprehensive vision of spiritual formation, became the dominant interpretive lens for nearly a millennium, profoundly shaping Western Christian thought.

4.2 Medieval and Reformation Debates: Compromise and Radicalism

During the medieval period, as the church became fully integrated with the political and social fabric of Christendom, the tension between the sermon's absolute demands and the realities of life in the world became more acute. To address this, scholastic theologians, most notably Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), refined and systematized what became known as the "Double Standard" view. This interpretation distinguished between two levels of ethical requirements within the sermon: "precepts," which were binding on all Christians for salvation (such as prohibitions against murder and adultery), and "counsels of perfection," which were optional but meritorious paths to a higher spiritual life (such as voluntary poverty, perfect chastity, and obedience to a spiritual superior). These counsels were seen as primarily applicable to the spiritual elite such as monks, nuns, and clergy, thus providing a theological framework that upheld the sermon's ideals while not imposing its most radical demands on the laity engaged in secular life.

The Protestant Reformation shattered this medieval consensus and produced a variety of new interpretive approaches.

-

Martin Luther (1483-1546), deeply concerned with avoiding any form of "works righteousness," rejected the distinction between precepts and counsels. Instead, he proposed his influential doctrine of the "Two Realms" (or two kingdoms). According to Luther, a Christian lives simultaneously in two realms: the spiritual kingdom of God and the temporal kingdom of the world. The Sermon on the Mount applies directly and absolutely to the Christian's personal life of faith and in their relationships with other believers (the spiritual realm). However, in the temporal realm, when acting in a public office (as a prince, soldier, judge, or even a parent), the Christian is bound by different obligations, namely, the preservation of justice and order, which may require the use of force or the passing of harsh judgments. This allowed Luther to maintain the sermon's authority in the personal sphere while justifying a Christian's participation in the often-compromising structures of secular society.

-

John Calvin (1509-1564) also sought to apply the sermon to the life of all believers but employed a different hermeneutical principle, the analogia fidei (analogy of faith). He argued that seemingly absolute statements in the sermon must be interpreted in light of the whole counsel of Scripture. For example, the prohibition against all oaths in Matthew 5:34 is moderated by other biblical passages where oaths are permitted or even used by figures like the Apostle Paul. This approach allowed for a more nuanced application of the sermon's commands to the complexities of life.

-

The Radical Reformation (Anabaptists) represented a third, starkly different path. Groups like the Mennonites rejected what they saw as the compromises of both the medieval church and the magisterial Reformers. They championed an absolutist and literal interpretation of the sermon, viewing it as the binding constitution for the church, which they understood as a voluntary community of committed disciples, separate from the fallen world. They embraced pacifism and non-retaliation ("turn the other cheek"), refused to swear oaths, and abstained from participation in civil government, which they saw as operating by the sword, an instrument forbidden to Christians. For the Anabaptists, the sermon was not an impossible ideal or a private ethic, but the practical, lived-out law of Christ's kingdom.

4.3 Modernity and Its Discontents: New Interpretive Frameworks

The modern period, marked by the Enlightenment, historical criticism, and secularization, gave rise to new interpretive frameworks that often sought to rationalize the sermon or re-situate its meaning within new philosophical contexts.

-

Protestant Liberalism, flourishing in the 19th century with figures like Adolf von Harnack, sought to distill the "timeless essence" of Jesus's teaching from its first-century Jewish context. This approach viewed the sermon not as a set of binding laws but as the supreme expression of universal ethical principles, primarily the fatherhood of God and the infinite value of the human soul. The focus shifted from literal obedience to the cultivation of an "inner disposition" (

Gesinnung) of love and humility. The sermon's purpose was to inspire a certain attitude, not to prescribe specific, unchangeable behaviors. -

A sharp reaction to this liberal optimism came from scholars who emphasized the apocalyptic worldview of Jesus. Albert Schweitzer, in his landmark work The Quest of the Historical Jesus, argued that Jesus's radical ethics were entirely conditioned by his mistaken belief that the end of the world was imminent. The sermon, therefore, was an "interim ethic", a set of emergency rules for the short period before the arrival of the kingdom. Because the end did not come as expected, Schweitzer concluded that these teachings were not intended as a permanent guide for Christian conduct in a continuing world history.

-

Another influential modern approach is Dispensationalism, systematized in the Scofield Reference Bible. This framework divides biblical history into distinct "dispensations" or economies of God's rule. In classic dispensationalism, the Sermon on the Mount is understood as "kingdom law," containing the constitution for the future millennial kingdom that Christ will establish on earth. It is therefore not directly applicable to believers in the current "church age," which is governed by the principle of grace as revealed in the Pauline epistles. While the sermon may contain valuable moral principles, its primary application is postponed to a future era, thus resolving the tension of its radical demands for the present-day Christian.

4.4 Contemporary Voices: The Call to Costly Discipleship

The 20th and 21st centuries have witnessed a powerful resurgence of interpretations that seek to reclaim the Sermon on the Mount as a direct and non-negotiable call to discipleship, often in reaction against the perceived compromises of earlier views.

The most significant voice in this movement was Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945). His book The Cost of Discipleship (originally Nachfolge, "Following After") is a sustained and passionate polemic against what he termed "cheap grace", the preaching of forgiveness without the call to repentance, grace without discipleship, and communion without confession. For Bonhoeffer, the Sermon on the Mount is the definitive articulation of this costly grace, which demands the believer's entire life in obedience to Jesus. He fiercely criticized interpretations like Luther's "Two Realms" doctrine, which he believed had been misused by the German church to justify passivity and complicity with the Nazi regime. He argued that there is only one reality, the reality of Christ and the call of the sermon is to a visible, concrete, and undivided obedience to Jesus in the midst of the world.

Following in this tradition, many contemporary theologians and ethicists from various traditions (including Anabaptist, Liberationist, and Neo-Orthodox) have returned to the sermon as the foundational text for Christian ethics. These interpretations emphasize its relevance for contemporary issues such as social justice, peacemaking and non-violence, economic inequality, and ecological stewardship. The sermon is read not as a private moral code or a future constitution, but as a public and political manifesto that challenges the dominant values and power structures of the present age. It continues to inspire believers to live as citizens of another kingdom, whose allegiance to their King transcends all other loyalties.

Conclusion: The Enduring Challenge of The Sermon On The Mount

The Sermon on the Mount is far more than a simple moral code or a collection of religious sayings. As this comprehensive analysis has demonstrated, it is a rich, multi-layered, and theologically profound proclamation of the reality of the Kingdom of God. It functions simultaneously on several levels: as the ethical constitution for the community of disciples, as a radical reinterpretation of God's law that exposes the depth of human sinfulness, as a supreme revelation of the person and authority of Jesus Christ, and as an urgent call to a life of costly, counter-cultural obedience.

Its historical and literary context within Matthew's Gospel establishes it as the inaugural address of the Messianic King, a New Moses delivering the definitive law from a New Sinai. The exegetical journey through its chapters reveals a coherent and escalating argument that moves from the internal character of a disciple (the Beatitudes) to the external manifestation of a higher righteousness in action and piety, culminating in an unavoidable call to decision. Theologically, it presents the ethic of an inaugurated eschatology, the standards of the age to come, to be lived out in the present tension of the "already and not yet."

The long and varied history of its interpretation reveals as much about the church as it does about the sermon itself. The persistent struggle to understand and apply its teachings reflects the enduring tension between the radical call of the kingdom and the pragmatic realities of the world. From Augustine's "perfect standard" to the compromises of medieval and Reformation thought, and from the absolutism of the Anabaptists to the various frameworks of modernity, each era has wrestled with its message.

Ultimately, the Sermon on the Mount remains the ultimate challenge to any form of Christianity that has grown too comfortable or has made its peace with the values of the world. It comforts the afflicted, the poor in spirit, the mourning, the persecuted by pronouncing them blessed and promising them the kingdom. At the same time, it afflicts the comfortable, the self-righteous, the powerful, the wealthy by demanding a righteousness that exceeds all human standards and a loyalty that tolerates no rivals. Its words continue to echo down from the mountain, calling every generation of hearers to make the fundamental choice: to build one's life on the shifting sands of conventional wisdom or on the unshakeable rock of hearing and obeying the words of the King.

Also see: